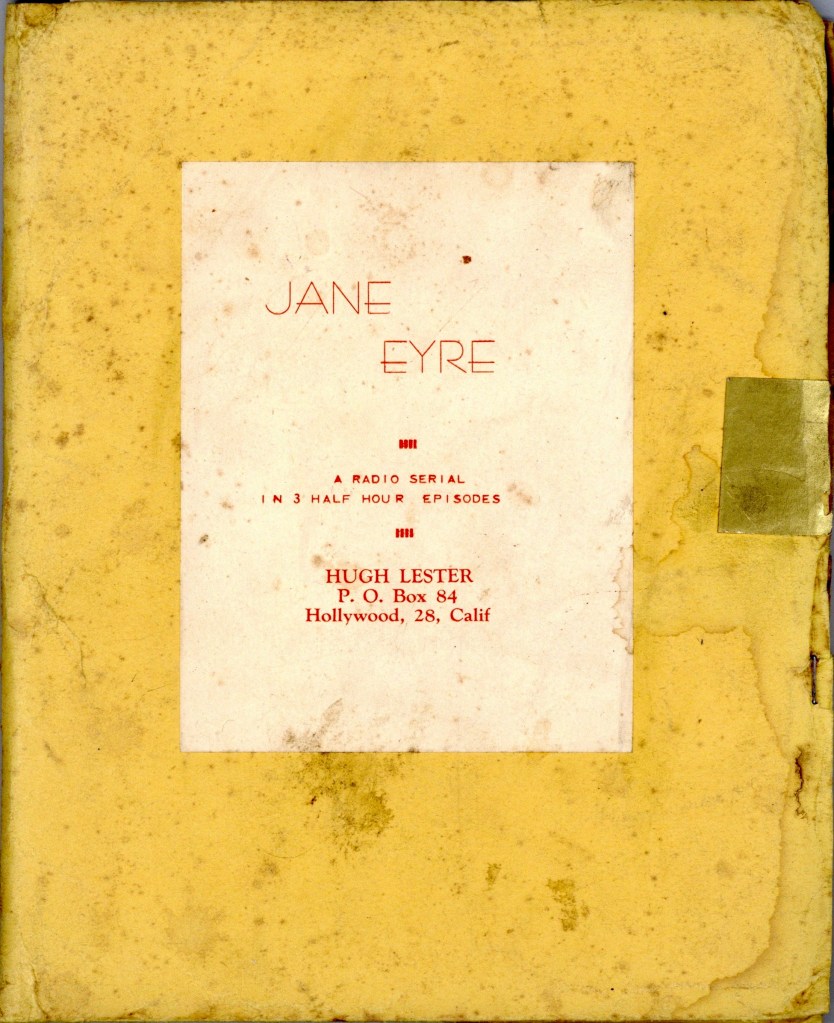

The most recent item to enter my collection of ephemera is a somewhat tattered, unpublished radio script (pictured above). It is held together by rusty staples that attest to the authenticity to which, as a cultural product, it cannot justly lay claim. I still do not know the first thing about it. When was it written? To whom was it sold? Was it ever produced?

Initial research online revealed at least that Hugh Lester, the writer claiming responsibility – or demanding credit – for the script, was by the late 1930s a known entity in the business of radio writing, with one of his adaptations (a fifteen-minute dramatisation of Guy de Maupassant’s story “The Necklace”) appearing in a volume titled Short Plays for Stage and Radio (1939). Rather than wait to ascertain its parentage, I decided to adopt Lester’s brainchild after spotting it lingering in the virtual orphanage known as eBay, where the unwanted are put on display for those of us who might be enticed to give them a new home.

Getting it home – my present residence – proved a challenge. After being dispatched from The Bronx, the script spent a few months in foster care – or a gap behind a sofa in my erstwhile abode in Manhattan – before my ex could finally be coaxed into shipping it to Wales. I occasionally have eBay purchases from the US mailed to my former New York address to avoid added international postage; but the current pandemic is making it impractical to collect those items in person, given that I am obliged to forgo my visits to the old neighborhood this year. I was itching to get my hands on those stapled sheets of paper, especially since I am once again teaching my undergraduate class (or module, in British parlance) in Adaptation, in which the particular story reworked by Lester features as a case study.

As its title declares, the item in question is a “Radio Serial in Three Half Hour Episodes” of Charlotte Brontë’s 1848 novel Jane Eyre. It is easy for us to call Jane Eyre that now – a novel. When it was first published, of course, it came before the public as an autobiography, the identity of its creator disguised (‘Edited by Currer Bell,’ the original title page read), leading to wild speculations as to its parentage. An adaptation, on the other hand, proudly discloses its origins, and it builds a case for its right to exist by drawing attention to its illustrious ancestry, as Lester’s undated serialisation does:

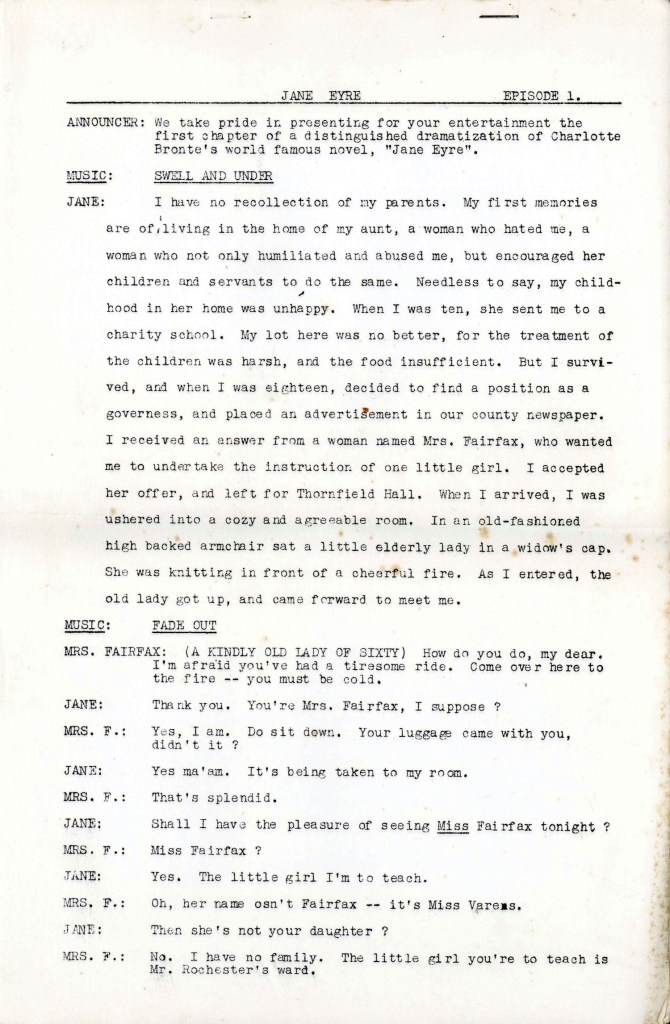

Announcer: We take pride in presenting for your entertainment at the first chapter of a distinguished dramatisation of Charlotte Brontë’s world famous novel, Jane Eyre.

An interesting choice of phrasing, that: while the source is pronounced to be ‘world-famous,’ meaning popular, this further popularisation by radio is argued to be ‘distinguished,’ meaning, presumably, first-rate – unless ‘distinguished’ is meant to suggest that the child (the adaptation) can readily be told apart from the parent (source). Is not Jane Eyre ‘distinguished,’ whereas the aim of radio serials, plays for a mass medium, is to be popular, if only temporarily? Clearly, Lester aimed in that announcement to elevate to an art the run-of-the-mill business of adaptation that was his line; and run-of-the-mill it certainly was, most or the time.

One expert on radio scripts, commenting in 1939, went so far as to protest that radio had ‘developed almost no writers,’ that it had ‘appropriated almost all of them, at least all of those who could tell a good story.’ The same commentator, Max Wylie – himself a former radio director of scripts and continuity at CBS – also called ‘radio writing’ the ‘orphan child of accepted literature.’ To him, most radio writing was no ‘radio’ writing at all, at least not ‘in the artistic and creative sense,’ but ‘an effort in translation’ – ‘a work of appropriation whose legitimacy depends upon the skill of its treatment but whose real existence depends upon the work of some able craftsman who quite likely never anticipated the electrical accident of the microphone.’

Instead of approaching adaptation in terms of fidelity – how close it is to its source – what should concern those of us who write about radio as a form is how far an adaptation (or translation, or dramatisation) needs to distance itself from its source so it can be adopted by the medium to which it is introduced. However rare they may be, radio broadcasts such as “The War of the Worlds” have demonstrated that an adaptation can well be ‘radio writing’ – as long as it is suited to the medium in such a way that it becomes dependent on it for its effective delivery. It needs to enter a new home where it can be felt to belong instead of being made to pay a visit, let alone be exploited for being of service.

Jane Eyre was adapted for US radio numerous times during the 1930s, ‘40s and early ‘50s. The history of its publication echoing the story of its heroine and their fate in the twentieth century – Jane Eyre was apparently parentless. Brontë concealed her identity so that Jane could have a life in print, or at least a better chance of having a happy and healthy one. In the story, Jane must learn to be independent before the man who loves her can regain her trust – a man who, in turn, has to depend on her strength. Similarly, Jane Eyre had to be separated from her mother, Charlotte Brontë, because she could not trust the male critics to accept her true parentage.

On the air, that parent, Charlotte Brontë, needs to be acknowledged so that an adaptation of Jane Eyre does not become an impostor; at the same time, the birth mother must be disowned so that Jane can become a child of the medium of which the parent had no notion – but which is nonetheless anticipated in the telepathic connection that, in the end, leads an adult and independent Jane back to Mr. Rochester, the lover who betrayed her and must earn her trust anew.

Lester’s three-part adaptation retains that psychic episode in Brontë’s story:

Rochester: (In agony. Whispering through a long tube) Jane! Jane! I need you. Come to me – come to me!

In radio broadcasting, ‘[w]hispering through a long tube’ can be made to suggest telephony and telepathy – and indeed the medium has the magic of equating both; the prosaic soundstage instruction revealing the trick makes clear, however, that the romance of radio is in the production, that, unlike a novel, a radio play cannot be equated with a script meant for performance.

Being three times as long as most radio adaptations, Lester’s script can give Jane some air to find herself and a home for herself. And yet, like many other radio versions of the period, it depends so heavily on dramatisation as to deny Jane the chance of shaping her own story. One scholar, Sylvère Monod has identified thirty passages in which the narrator of Jane Eyre – Jane Eyre – directly addresses the audience. And yet, the most famous line of Brontë’s novel is missing from Lester’s script, just as it is absent in most adaptations: ‘Reader, I married him.’ How easily this could be translated into ‘listener’ – to resonate profoundly that most intimate of all mass media: the radio.

Lester, according to whose script plain Jane is ‘pretty,’ is not among the ‘distinguished’ plays of – or for – radio. Exploiting its source, by then a copyright orphan, it fosters an attitude that persists to this day, despite my persistent efforts to suggest that it can be otherwise: that radio writing is the ‘orphan child of accepted literature.’

Well, I am feeling strangely liberated. A few days ago, I learned that my BlogMad account had been wiped out as a result of some database corruption—a common occurrence, if comments from fellow web journalists are any indication. I chose not to sign up anew right away, luxuriating instead in the thought of temporarily forgoing those new-fangled ways in favor of an old-fashioned book. Despite my doctorate in literature, I don’t read nearly as much as I ought to these days. So, I took advantage of the first warm day of the season, ripped off my shirt, and grabbed . . . a Trollope. Anthony Trollope, that is, who happens to be one of my favorite authors. Recently, I picked up his Cousin Henry (my, doesn’t this begin to sound so Carry On!) after discovering that this novel is set in Wales, that strange and wild country west of England I am still struggling to call my home.

Well, I am feeling strangely liberated. A few days ago, I learned that my BlogMad account had been wiped out as a result of some database corruption—a common occurrence, if comments from fellow web journalists are any indication. I chose not to sign up anew right away, luxuriating instead in the thought of temporarily forgoing those new-fangled ways in favor of an old-fashioned book. Despite my doctorate in literature, I don’t read nearly as much as I ought to these days. So, I took advantage of the first warm day of the season, ripped off my shirt, and grabbed . . . a Trollope. Anthony Trollope, that is, who happens to be one of my favorite authors. Recently, I picked up his Cousin Henry (my, doesn’t this begin to sound so Carry On!) after discovering that this novel is set in Wales, that strange and wild country west of England I am still struggling to call my home.