I don’t often indulge in morning afterthoughts. I might—and frequently do—revise what I said (or, rather, how I said it); but I generally just take time, and one time only, to say my piece instead of doling it out piecemeal. Unlike the producers of much of the (un)popular culture I go on about here, I don’t make a virtue of saying “As I was saying” or make my fortune, say, by milking the cash cow of regurgitation. To my thinking, which is, I realize, incompatible with web journalism, each entry into this journal, however piffling, should be complete—a composition, traditionally called essay, that has a beginning, middle and end, a framework that gives whatever I write a raison d’être for ending up here to begin with.

Although I resist following up for the sake of building a following, it does not follow that my last word in any one post is the last word on any one subject—especially if the subject is as inexhaustible as the Eurovision Song Contest, which festival of song, spectacle and politics compelled me previously to go on as follows: “It [a Eurovision song] is, at best, ambassadorial—and the outlandish accent of the German envoy makes for a curious diplomatic statement indeed.”

Diplomatic blunder, my foot. My native Germany did win, after all, coming in first for the first time since 1982, when Germany was still divided by a wall so eloquent that, growing up, I did not consider whatever lay to the east of it German at all. Apparently, this year’s German singer-delegate Lena Meyer-Landrut, born some time after that wall came down, did not step on anyone’s toes with her idiosyncratic rendition of “Satellite,” a catchy little number whose inane English lyrics she nearly reduced to gibberish.

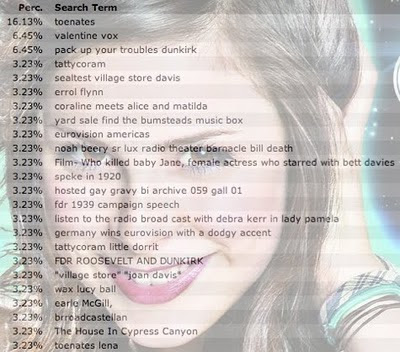

Her aforementioned insistence on turning toenails into “toenates” intrigued a number of bemused or irritated viewers to go online in search of answers, only to be directed straight to broadcastellan. Perhaps, the United Kingdom should have fought tooth and nates instead of articulating each tiresome syllable of their entry into the competition, a song so cheesy that it did not come altogether undeservedly last, even if European politics surely factored into the voting.

Britain never embraced European unity wholeheartedly—and those in the thick of the economic crisis now challenging the ideal of Europe may well resent it. Is it a coincidence that the votes were cast in favor of the entrant representing the biggest economy in Europe, a country in the heart of the European continent?

While not content, perhaps, to orbit round that center of gravity, other nations may yet feel that it behoves them to acknowledge the star quality of Germany, which, according to contest rules, is called upon to stage the spectacle in 2011. After all, why shouldn’t the wealthiest neighbor be host of a competition some countries, including Hungary and the Czech Republic, declared themselves too cash-strapped even to enter this year.

I may not have been back on native soil since those early days of German reunification, but there was yet some national pride aroused in me as “Satellite” was declared the winner of the contest by the judges and juries of thirty-eight nations competing in Oslo this year along with Deutschland.

That said, seeing a German citizen draped in a German flag as she approaches the stage to take home a coveted prize, however deserved, still makes me somewhat uneasy. Given our place in world history, the expression of national pride strikes me as unbecoming of us, to say the least. I was keenly aware, too, that there were no points awarded to Germany by the people of Israel.

Will I ever stop being or seeing myself as a satellite and, instead of circling around Germany, get round to dealing with my troubled relationship with the country I cannot bring myself to call home? That, after the ball was over, formed itself as a sobering afterthought. And that, for the time being, is the beginning, middle, and end of it. Truth is, I take comfort putting a neat frame around pictures that are hazy, disturbing or none too pretty.

“I’m in love with a fairy tale / Even though it hurts.” It was with these lyrics, a fiddle, and a disarming smile that Norwegian delegate Alexander Rybak came to be voted winner of the 54th Eurovision Song Contest—an annual spectacle-cum-diplomatic mission reputed to be the world’s most-watched non-sporting event on television. However intended, the lines aptly capture the attitude of many Europeans toward the contest, just as the entries in the ever expanding competition are a reflection of all that is exasperating, perverse, and wonderful about European Unity—a leveling of cultures for the sake of political stability, national security, and economic opportunity.

“I’m in love with a fairy tale / Even though it hurts.” It was with these lyrics, a fiddle, and a disarming smile that Norwegian delegate Alexander Rybak came to be voted winner of the 54th Eurovision Song Contest—an annual spectacle-cum-diplomatic mission reputed to be the world’s most-watched non-sporting event on television. However intended, the lines aptly capture the attitude of many Europeans toward the contest, just as the entries in the ever expanding competition are a reflection of all that is exasperating, perverse, and wonderful about European Unity—a leveling of cultures for the sake of political stability, national security, and economic opportunity.

Well, I am mad about music this weekend, or something remotely resembling it. After fifteen years of going without while living in the Eurotrash-resisting US, I finally got another hit of it last spring. The Eurovision Song Contest, I mean, the spectacle (or cultural war) in whose battles have fought the likes of Celine Dion, Olivia Newton-John, Abba, Lulu, Cliff Richards, Katrina and the Waves, and whoever it was first to belt out “Volare.” Thursday night’s semi-finals in Athens were predictably vulgar—short on fabric and long on fanfare, feuds and fanaticism.

Well, I am mad about music this weekend, or something remotely resembling it. After fifteen years of going without while living in the Eurotrash-resisting US, I finally got another hit of it last spring. The Eurovision Song Contest, I mean, the spectacle (or cultural war) in whose battles have fought the likes of Celine Dion, Olivia Newton-John, Abba, Lulu, Cliff Richards, Katrina and the Waves, and whoever it was first to belt out “Volare.” Thursday night’s semi-finals in Athens were predictably vulgar—short on fabric and long on fanfare, feuds and fanaticism. Well, it’s one of those drab and dispiriting whatever-happened-to-summer kind of days on which even morale-boosting Carmen Miranda might have thrown in the technicolored towel. Yesterday, the house was shrouded in mist; and now, as if to mock the recently announced drought warning and water restrictions, the slow-moving clouds across the Welsh hills have assumed a washed-out shade of gray that looks about as cheerful as the fur of a middle-aged rat trying to waddle off with your last piece of cheese. Not that there was any more merriment to be had last night when I lowered the blind to screen the less-than-classic Mae West vehicle The Heat’s On (1943).

Well, it’s one of those drab and dispiriting whatever-happened-to-summer kind of days on which even morale-boosting Carmen Miranda might have thrown in the technicolored towel. Yesterday, the house was shrouded in mist; and now, as if to mock the recently announced drought warning and water restrictions, the slow-moving clouds across the Welsh hills have assumed a washed-out shade of gray that looks about as cheerful as the fur of a middle-aged rat trying to waddle off with your last piece of cheese. Not that there was any more merriment to be had last night when I lowered the blind to screen the less-than-classic Mae West vehicle The Heat’s On (1943).