For the reward of a single dollar, readers of Movie-Radio Guide used to send in “boners”—fluffed or unintentionally funny lines they had caught on the air. On 29 Feburary 1940, for instance, Olive Doeling of Petaluma, California, tuned in to station KGO and heard Benny Walker (Benny Walker?) say: “Wish you could see her, folks. She’s lugging a saxophone almost as big as she is behind her.” Another buck went to a listener from Jackson, Mississippi, who reported the following exchange between Major Bowes and a contestant on his Amateur Hour broadcast from 7 June 1936:

For the reward of a single dollar, readers of Movie-Radio Guide used to send in “boners”—fluffed or unintentionally funny lines they had caught on the air. On 29 Feburary 1940, for instance, Olive Doeling of Petaluma, California, tuned in to station KGO and heard Benny Walker (Benny Walker?) say: “Wish you could see her, folks. She’s lugging a saxophone almost as big as she is behind her.” Another buck went to a listener from Jackson, Mississippi, who reported the following exchange between Major Bowes and a contestant on his Amateur Hour broadcast from 7 June 1936:

CONTESTANT. I was a dressmaker’s model and then I married.

MAJOR. Wholesale or retail?

Reading lines like these makes me want to tune in the original program, to find the recording and hear for myself.

The other day, when I read that Mary Livingstone was supposed to have giggled “Jack, I’ll never forget the look on that ski house when it saw your face,” I wondered whether that was indeed what she had said and how her husband, the cast, and the studio audience had responded. Listening to a recording of the 25 February 1940 broadcast of the Jell-O Program, I heard no such fluff. “I’ll never forget the impression on your face when you crashed in the ski house,” Livingstone said instead. Had J. N. Lawrence from San Diego earned that dollar? Was the “boner” bona fide or bogus?

Well, before accusing any of those tuners-in, I had to remind myself that many of the live programs of the past were staged twice—once for the East Coast, then for the West. What J. N. Lawrence had picked up on California was not what anyone living East could have heard—or anyone listening to a recording of the East Coast broadcast.

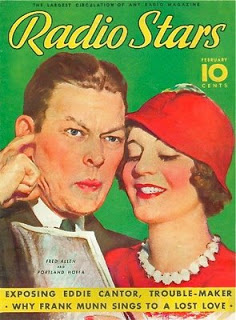

How different the two broadcast could be was demonstrated on 20 March 1940, when a certain Mr. Ramshaw caused a riot on the Fred Allen Show. Mr. Ramshaw was a celebrated Golden Eagle who toured the US with his British trainer, falconer Captain C. W. R. Knight. The Captain was encouraged by Allen to let the Mr. Ramshaw fly around in the studio; but, as it turned out, he had little success in convincing the bird to return to him as rehearsed—and not until he had left his mark on the members of the audience assembled in studio 8-H, Radio City, New York.

Actually, as Allen recalled in Treadmill to Oblivion, Mr. Ramshaw had narrowly “missed the shoulder of a student who had come down from Fordham University to advise [Allen] that [he] had won a popularity poll at the school.”

Responding to a complaint from the vice president of NBC, a less than apologetic Allen remarked: “i thought i had seen about everything in radio but the eagle had a trick up his feathered colon that was new to me,” to which he added: “i know you await with trepidation the announcement that i am going to interview sabu with his elephant some week.”

There was no getting back to the script that evening; and the commotion that ensued was another forceful reminder that, for all his talent as a writer, Allen was in even finer feather when he did not have to stick to the ink from his mechanized quill. Now, winging it, or flying by the seat of one’s pants, was not condoned by those who footed the bill of comedy-variety programs and kept an eagle eye on their production. Everything had to be performed as scripted—and strictly within the time allotted for each number, sketch, and broadcast.

So, when Allen had to repeat his program three hours later—at midnight—for the West Coast audience, the spokesperson of Young and Rubicam, the advertising agency working on behalf of the show’s sponsor, did not permit Mr. Ramshaw to make an encore. The segment was out, and, as Stuart Hample (author of “all the sincerity in hollywood” told Max Schmid in a 4 November 2001 interview over WBAI, New York, Allen was forced to revise the script and remove the offending segment.

Allen defended his feathered guest by claiming that Mr. Ramshaw had resented the censor’s “dictatorial order” and, “deprived by nature of the organs essential in the voicing of an audible complaint, called upon his bowels to wreck upon us his reaction to [Mr. Royal’s] martinet ban.”

The feather “l’affaire eagle” added to Allen’s cap never got to tickle his West Coast listeners. Network radio programs may have had a coast-to-coast audience; but, be it an eagle, a turkey, or a lark, some of what took off or managed to escape in the East could never fly or land in the West.

Related recordings

Fred Allen Show, 20 March 1940

Earlier this week, while travelling through the ancient Catskill Mountains—which, truth be told, are not nearly as shadowy and mysterious as the Welsh countryside—we happened upon the Kaaterskill Falls, the very sight of the extraordinary episode in the life of the legendary idler. We retraced his steps, stumbling over the rocks and trees that nature has so liberally and carelessly strewn upon this secluded spot. The hike was tiring enough; but that could hardly account for the fatigue I have been experiencing ever since our return to Wales. A long forgotten lecture by a venerable physician appears to provide the answer.

Earlier this week, while travelling through the ancient Catskill Mountains—which, truth be told, are not nearly as shadowy and mysterious as the Welsh countryside—we happened upon the Kaaterskill Falls, the very sight of the extraordinary episode in the life of the legendary idler. We retraced his steps, stumbling over the rocks and trees that nature has so liberally and carelessly strewn upon this secluded spot. The hike was tiring enough; but that could hardly account for the fatigue I have been experiencing ever since our return to Wales. A long forgotten lecture by a venerable physician appears to provide the answer.

As much as I dislike mathematics and however arithmetically challenged I am without a calculator, I very much enjoy compiling lists and studying figures such as box office statistics. I am less interested in watching contemporary film than in finding out how many others have. It gives me an idea of what is popular without having to subject myself to yet another sequel of an indifferently constructed CGI clones. My kind of picture is, on average, at least half a century old. Today, I considered the list of films I have screened of late and rated them, on a scale from one to ten, at the Internet Movie Database. It is not an easy task, this kind of opining by the numbers, as I

As much as I dislike mathematics and however arithmetically challenged I am without a calculator, I very much enjoy compiling lists and studying figures such as box office statistics. I am less interested in watching contemporary film than in finding out how many others have. It gives me an idea of what is popular without having to subject myself to yet another sequel of an indifferently constructed CGI clones. My kind of picture is, on average, at least half a century old. Today, I considered the list of films I have screened of late and rated them, on a scale from one to ten, at the Internet Movie Database. It is not an easy task, this kind of opining by the numbers, as I  Not that I am entirely visual-minded on this my day of reckoning. Once again, I am cataloguing my library of books on broadcasting, a collection that has grown considerably since last I attempted to inventory it. While I am at it, I am scanning some of the covers, so aptly referred to as dust jackets and put them on display where they are more likely to tickle someone’s fancy rather than irritate throat and eye. Pictured are first editions of Francis Chase’s Sound and Fury: An Informal History of Broadcasting (1942), Charles Siepmann’s Radio’s Second Chance (1946), and fred allen’s letters, edited by Joe McCarthy (1965).

Not that I am entirely visual-minded on this my day of reckoning. Once again, I am cataloguing my library of books on broadcasting, a collection that has grown considerably since last I attempted to inventory it. While I am at it, I am scanning some of the covers, so aptly referred to as dust jackets and put them on display where they are more likely to tickle someone’s fancy rather than irritate throat and eye. Pictured are first editions of Francis Chase’s Sound and Fury: An Informal History of Broadcasting (1942), Charles Siepmann’s Radio’s Second Chance (1946), and fred allen’s letters, edited by Joe McCarthy (1965). There is “no glory in radio,” Allen remarked in a letter to Abe Burrows (

There is “no glory in radio,” Allen remarked in a letter to Abe Burrows (

Well, leave it to a couple of old troupers to make me feel a little less sorry for myself. This New Year’s cold is making me feel miserable, cranky, and just about as fresh as a Jackie Mason standup routine. As those subjected to my groanings and whinings will only be too glad to corroborate, I am not one to suffer in silence. Mind you, I groan and whine even without an audience, of which I was deprived this afternoon (save for our terrier, Montague, who showed no signs of interest, let alone compassion). I reckon those noises serve chiefly as a reminder to myself that I am still numbering among the living.

Well, leave it to a couple of old troupers to make me feel a little less sorry for myself. This New Year’s cold is making me feel miserable, cranky, and just about as fresh as a Jackie Mason standup routine. As those subjected to my groanings and whinings will only be too glad to corroborate, I am not one to suffer in silence. Mind you, I groan and whine even without an audience, of which I was deprived this afternoon (save for our terrier, Montague, who showed no signs of interest, let alone compassion). I reckon those noises serve chiefly as a reminder to myself that I am still numbering among the living.