On my only trip requiring an overnight bag during this stay-at-home summer, my husband and I drove from our patch on the west coast of Britain to the thoroughly overcrowded Cotswolds and, upon my urging, made a stop-over at the Welsh town of Hay-on-Wye, an internationally renowned haven for second-hand book lovers. Now, musty old volumes and COVID-19 do not quite go together – or so I thought – considering that retail spaces generally set aside for them are rarely supermarket-sized. However, Hay, which depends on the trade, managed to make it work; and, meeting the moment by donning a mask, I got to enjoy an afternoon of socially distanced and sanitized hands-on browsing.

Not that I walked away with any tomes of consequence. While at the Cinema bookstore – a shop not limited to publications related to motion pictures – I discovered a nook stacked with a curious assortment of ephemera: German movie programs of the 1930s. I am not sure how they ended up in a Welsh bookshop – but that dislocation may well have extended their shelf life … until a German such as I came along and took an Augenblick to sift through them.

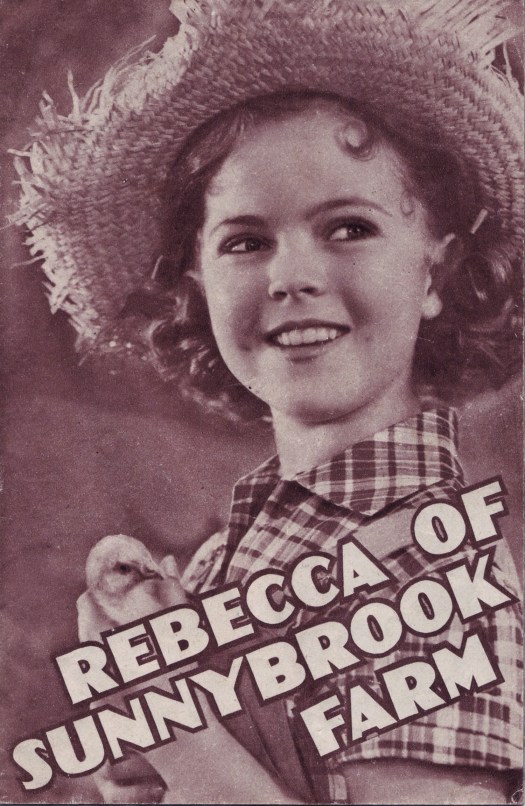

The program pictured above, dating from 1937, left me puzzled for a while. I am familiar with many of Shirley Temple’s features – but I did not recall any among them bearing a title remotely like “Shirley auf Welle 303,” or “Shirley over Station 303.” So, I picked up this fragile brochure, and a few others besides, if mainly to tap their potential as pop cultural conversation pieces.

The film being deemed worthy of commemoration is Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, a DVD of which is gathering dust in my video library. The title refers to an early twentieth-century children’s literature classic, although the movie version bears so little resemblance to it that it could hardly be considered an adaptation. Not that the title of the novel would have resonated with German audiences. Meeting this challenge, the marketing people at Fox came up with a new one that might sound more relatable.

I suspect that the servants of the Nazi regime would have objected to the name of the titular character as well, being that Rebecca is Hebrew in origin, meaning “servant of God.” Shirley, on the other hand, was a household name, Ms. Temple having charmed audiences around the world since at least 1934. Like the titles of several other Shirley Temple vehicles released in 1930s Germany, the German version of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm therefore bears the first name of its star. Only Heidi stayed Heidi, rather than being translated into “Little Swiss Miss Shirley.”

And yet, the effort to make the film seem more relatable to Nazi Germany’s picture-goers nonetheless resulted in a title that was out of touch with Fascist reality. In 1938, when the film was released in German cinemas, the idea of using radio transmitters for your purposes – or for the purpose of exploiting a child for your own purposes – was inimical to state-controlled broadcasting. On the air, it was always “Germany Calling,” a phrase famously used by the aforementioned Lord Haw-Haw beginning in 1939.

Germans would have struggled in vain to twist the dial and hit on a broadcast like Shirley’s, or they would have paid a price for such twisting. Many of them listened via the Volksempfänger, a mass-produced receiver that was always tuned in to the Führer’s voice. Imagine staying tuned to Fox News all day. Then again, so many who do have the choice not to still do nonetheless, not unlike those who were complaisant during the rise of Fascism in Germany.

The change in title – and the recontextualization it achieves – is peculiar, and only a performer as innocuous as Shirley Temple could have gotten away with what otherwise would have been downright seditious: seizing the microphone and taking to the airwaves in a makeshift studio set up in a remote farmhouse. Perhaps, the titular bandwidth – 303 – was to signal that Shirley’s broadcast had been sanctioned after all, 30 January 1933 being the date Hitler came to power. In the Third Reich, three was heralded as the charm.

For decades, the German film industry did wonders – or, rather, wilful damage – to international films with its dubbing of their soundtracks; voicing over and voiding the content of the source, there were many opportunities to ready a film more substantive than Rebecca for consumption in Nazi Germany. I do not recall seeing this movie in my native language, although I do remember a festival of her films airing on West German television in the late 1970s. Not that watching Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm in the original is an experience I am eager to repeat, clobbered together a vehicle for an overhyped and overworked child star about to wear out her welcome that it is. Variety dismissed the film at the time as a “weak story,” “indifferently acted and directed,” while claiming its lead to be “at her best.”

The German program does little more than summarize the plot as well as state the principal actors and main players behind the scene of the production; I am sure someone checked whether producer Darryl F. Zanuck was Jewish, which he was not. What struck me about the program was that it mentions the word ‘propaganda’ twice in the first paragraph, where it was used as a substitute for advertising (in German, “Werbung” or “Reklame”). Sending up the excesses of US consumerism while promoting the ostensible virtues of country living, this trifle of a film – distributed in Nazi Germany by the enterprising and accommodating “Deutsche” Fox – could serve as a vehicle for anti-American propaganda at a time when increasingly few US films were granted a release in Germany.

By making such trifles, and by marketing them for distribution in Nazi Germany, the US film industry contributed to the rise of Fascism, which, only after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hollywood films began to confront with a suitably glossy vengeance. By that time, US films were banned in Germany, and Shirley Temple ceased to be a leading lady – at least in motion pictures.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous. The man behind the counter looked none too pleased when I handed over my money. This one, he said, had escaped him. The item in question is a rare little volume on radio drama, written way back in 1929, at a time when wireless theatricals were largely regarded, if at all, as little more than a novelty. In his foreword, Productions Director for the BBC, R. E. Jeffries, expressed the not unfounded belief that its author, one Gordon Lea, had the “distinction of being the first to publish a work in volume form upon the subject.”

The man behind the counter looked none too pleased when I handed over my money. This one, he said, had escaped him. The item in question is a rare little volume on radio drama, written way back in 1929, at a time when wireless theatricals were largely regarded, if at all, as little more than a novelty. In his foreword, Productions Director for the BBC, R. E. Jeffries, expressed the not unfounded belief that its author, one Gordon Lea, had the “distinction of being the first to publish a work in volume form upon the subject.”