I am no historian. At least not in a traditional facts-and-figures sense. Early in life, I became doubtful of efforts to account for the present by recounting the past of a place or a people. Growing up – and growing up queer – in Germany during the 1970s and 80s, I was not encouraged to find myself in such accounts. After all, how could I have developed a sense of being part of a national history? The present did not make me feel representative even of my own generation, while the then still recent past was presented to me as the past of a different country. A different people, even. A people whose history was not only done but dusted to the point of decontamination.

That many of those people – those old or former Nazis – were all around me and that the beliefs they held did not get discarded like some tarnished badge was apparently too dangerous a fact to instill. Pupils would have turned against their teachers. Children would have come to distrust their parents. They might even have joined the left-wing activists who were terrorizing Germans for reasons about which we, endangered innocents and latent dangers both, were kept in the dark.

As I have shared here before – though never yet managed adequately to convey – I left Germany in early adulthood because I felt uneasy about my relationship with a country I could not bring myself to embrace as mine. It’s been a quarter of a century since I moved away, first to the US and then to Wales. For over two decades, I could not even conceive of paying the dreaded fatherland a visit.

Eventually, or rather suddenly, that changed. In recent years, I have found myself accepting offers to teach German language, history and visual culture, assignments that made me feel like a fraud for being second-hand when imparting knowledge about my birthplace. I realized that I needed to confront the realities from which I had been anxious to dissociate myself.

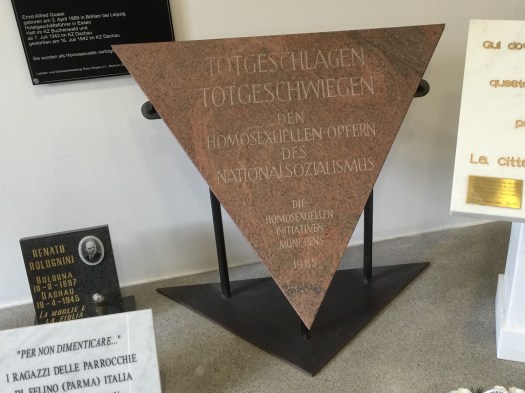

A memorial to the homosexuals killed during

the Nazi regime, made in the year I came out.

This summer, I visited the Dachau concentration camp for the first time. There, in the face of monumental horrors, I was drawn to one of the smallest and seemingly most inconsequential object on display: a cigarette card featuring the likeness of 1930s Hollywood actress Joan Blondell.

Dates and figures are no match for such a fragile piece of ephemera. To be sure, the macabre absurdity of finding a mass-manufactured collectible—purchased, no less, at the expense of its collector’s health—preserved at a site that was dedicated to the physical torture of real people and the eradication of individuality could hardly escape me.

But it was not this calculated bathos alone that worked on me. It was the thought that I, too, would have collected such a card back then, as indeed I do now. Investing such a throwaway object with meaning beyond its value as a temporary keepsake, I can imagine myself holding on to it as a remnant of a world under threat.

Unexpectedly, a picture of Joan Blondell

Looking at that photograph of Joan Blondell at Dachau, it was not difficult for me to conceive that, had I been born some forty years earlier, I might have been sent there, or to any one of the camps where queers like me were held, tortured and killed. That minor relic, left behind in the oppressive vastness of the Dachau memorial site, speaks to me of the need to take history personal and of the importance of discarding any notion of triviality. For me, it drives history where it needs to hit: home—home, not as a retreat from the world but as a sense of being inextricably enmeshed in it.

Joan Blondell, meanwhile, played her part fighting escapism by starring in “Chicago, Germany,” an early 1940s radio play by Arch Oboler that invited US Americans to imagine what it would be like if the Nazis were to win the war.

I rarely hear from my sister; sometimes, months go by without a word between us. I have not seen her in almost a decade. Like all of my relatives, my sister lives in Germany. I was born there. I am a German citizen; yet I have not been “home” for nearly twenty years. It was back in 1989, a momentous year for what I cannot bring myself to call “my country,” that I decided, without any intention of making a political statement about the promises of a united Deutschland, I would leave and not return in anything other than a coffin. I don’t care where my ashes are scattered; it might as well be on German soil—a posthumous mingling of little matter. This afternoon, my sister sent me one of her infrequent e-missives. I was sitting in the living room and had just been catching up with the conclusion of an old thriller I had fallen asleep over the night before. The message concerned US President Obama’s visit to Buchenwald, the news of which had escaped me.

I rarely hear from my sister; sometimes, months go by without a word between us. I have not seen her in almost a decade. Like all of my relatives, my sister lives in Germany. I was born there. I am a German citizen; yet I have not been “home” for nearly twenty years. It was back in 1989, a momentous year for what I cannot bring myself to call “my country,” that I decided, without any intention of making a political statement about the promises of a united Deutschland, I would leave and not return in anything other than a coffin. I don’t care where my ashes are scattered; it might as well be on German soil—a posthumous mingling of little matter. This afternoon, my sister sent me one of her infrequent e-missives. I was sitting in the living room and had just been catching up with the conclusion of an old thriller I had fallen asleep over the night before. The message concerned US President Obama’s visit to Buchenwald, the news of which had escaped me. “Enjoy the movie.” That is the response we get when we tell friends and acquaintances that we are on our way to the cinema. And while it is true that we generally seek enjoyment, whether by looking at separated lovers or severed heads, movie-going can be a disconcerting, unsettling event well beyond the shocks and jolts provided by horror and romance. The Boy with the Striped Pyjamas (a British film in its British spelling), is likely to be such an experience to anyone with a pulse and a sense of humanity ready for the tapping. To me, it was nothing short of devastating. I am not resorting to hyperbole when I say that I was rendered speechless; those accompanying me can attest to my disquietude. It has been a decade since last I watched a film (Saving Private Ryan) that has stirred and traumatized me to such a degree that, coming out of the theater, I felt sick to my stomach. No wonder. I had just been coerced into walking straight into the gas chamber of a concentration camp.

“Enjoy the movie.” That is the response we get when we tell friends and acquaintances that we are on our way to the cinema. And while it is true that we generally seek enjoyment, whether by looking at separated lovers or severed heads, movie-going can be a disconcerting, unsettling event well beyond the shocks and jolts provided by horror and romance. The Boy with the Striped Pyjamas (a British film in its British spelling), is likely to be such an experience to anyone with a pulse and a sense of humanity ready for the tapping. To me, it was nothing short of devastating. I am not resorting to hyperbole when I say that I was rendered speechless; those accompanying me can attest to my disquietude. It has been a decade since last I watched a film (Saving Private Ryan) that has stirred and traumatized me to such a degree that, coming out of the theater, I felt sick to my stomach. No wonder. I had just been coerced into walking straight into the gas chamber of a concentration camp.