Well, the scheduled power outage has been postponed due to regional flooding. I ought to be thankful, I guess, for one of the dreariest, wettest, and stormiest autumns ever to be weathered by the umbrella of a smile. Last night I was tolerably amused watching You’ll Find Out (1940), one of those star-studded Hollywood efforts whose chief purpose was to exploit and ostensibly promote the burgeoning radio industry by supplying listeners with images the mind’s eye could have very well done without. While the headliner of the movie, bandleader Kay Kyser, made my head ache with his bargain basement Harold Lloyd antics, the lavishly produced horror-comedy—co-starring Bela Lugosi, Peter Lorre, and Boris Karloff—nonetheless kept me in my seat.

Well, the scheduled power outage has been postponed due to regional flooding. I ought to be thankful, I guess, for one of the dreariest, wettest, and stormiest autumns ever to be weathered by the umbrella of a smile. Last night I was tolerably amused watching You’ll Find Out (1940), one of those star-studded Hollywood efforts whose chief purpose was to exploit and ostensibly promote the burgeoning radio industry by supplying listeners with images the mind’s eye could have very well done without. While the headliner of the movie, bandleader Kay Kyser, made my head ache with his bargain basement Harold Lloyd antics, the lavishly produced horror-comedy—co-starring Bela Lugosi, Peter Lorre, and Boris Karloff—nonetheless kept me in my seat.

You’ll Find Out makes much use of one of radio’s most intriguing technological novelties: the Sonovox. A patented sound effects device, the Sonovox could invest a trombone, a locomotive, or even a few raindrops (in short, anything capable of producing sound) with the power of human speech. Now, if only that deuced infant would speak up and let us know what it’s all about.

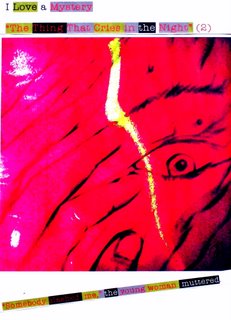

I am referring, of course, to the mysterious “Thing” in Carlton E. Morse’s I Love a Mystery serial “The Thing That Cries in the Night,” an old-time radio thriller I have been following for nearly two weeks now. On this day, 10 November, in 1949, the “Thing” made itself heard once again, announcing imminent death. When the Martin household’s peculiar baby alarm goes off tonight, another life is being claimed . . . the life of the prime suspect.

It is a thrilling twist in a story that, for two chapters, assumed the guise of a whodunit. In the previous installment, Job Martin, the heretofore good-natured drunk, was exposed as an ill-tempered cynic who showed little affection for his three tormented siblings. His youngest sister, Charity, promises to get a confession out of him, claiming that he was responsible for the murder of the Martin’s chauffeur. She urges Jack Packard, the man hired to investigate the mysterious goings-on, to round up all members of the household in the dining room.

Once they are assembled, Grandmother Martin insists on the observance of the family’s traditional seating arrangements. When the conference is just about to commence, the lights go out; yet no one has been within ten feet of the switch. The “Thing” begins to cry. It is not until the light is being turned on again that a gun goes off and Job is shot through the head.

This is the first murder committed in our presence. We are in the thick of it and, like the three members of the A-1 Detective Agency, left very much in the dark, despite the fact that the Martins and two of their hired investigators were standing right there in a brightly lit room when the shot was fired.

New questions arise: Was Job indeed the murderer of the Martin’s blackmailing hoodlum of a chauffeur? If so, he dodged the electric chair by taking that seat. Was he being silenced by one of his accomplices? If so, he must have been harboring a secret whose revelation is dangerous to another. Or is the “Thing” an otherwordly avenger of the sins committed in the house of Martin, a house doomed to fall?

Say, where were you when the lights went out?

Well, I am still hoping other internet tourists will join me in rediscovering I Love a Mystery beginning this Halloween (

Well, I am still hoping other internet tourists will join me in rediscovering I Love a Mystery beginning this Halloween (