“There’s no family uniting instinct, anyhow; it’s habit and sentiment and material convenience hold families together after adolescence. There’s always friction, conflict, unwilling concessions. Always!” Growing up in a familial household whose microclimate was marked by the extremes of hot-temperedness and bone-chilling calculation, I amassed enough empirical evidence to convince me that this observation—made by one of the characters in Ann Veronica (1909), H. G. Wells’s assault on Victorian conventions—is worth reconsidering. It is not enough to say that there is no “family uniting instinct.” What is likely the case during adolescence, rather than afterwards, is that the drive designed to keep us from destroying ourselves becomes the one that drives us away from each other. Depending on the test to which habit, sentiment and convenience are put, this might well constitute a family disuniting instinct.

“There’s no family uniting instinct, anyhow; it’s habit and sentiment and material convenience hold families together after adolescence. There’s always friction, conflict, unwilling concessions. Always!” Growing up in a familial household whose microclimate was marked by the extremes of hot-temperedness and bone-chilling calculation, I amassed enough empirical evidence to convince me that this observation—made by one of the characters in Ann Veronica (1909), H. G. Wells’s assault on Victorian conventions—is worth reconsidering. It is not enough to say that there is no “family uniting instinct.” What is likely the case during adolescence, rather than afterwards, is that the drive designed to keep us from destroying ourselves becomes the one that drives us away from each other. Depending on the test to which habit, sentiment and convenience are put, this might well constitute a family disuniting instinct.

Not even a mother’s inherent disposition toward her child—to which no analogous response exists in the offspring, particularly once the expediencies that appear to increase its chances of survival are being called into question—is equal to the impulse of self-preservation. I was twenty when I made that discovery; the discovery that there was no love lost between my mother and myself, or, rather, that whatever love or nurturing instinct, on her part, there had been was lost irretrievably.

Years ago, I tried to capture and let go of that moment in a work of fiction:

An early evening in late October. She stands in the dimly lit hallway, a dinner fork in her right hand, blocking the door, the path back inside. The memory of what caused the fight is erased forever by its emotional impact, its lasting consequences. The implement, picked up from the dining table during an argument (some trifle, no doubt, of a nettlesome disagreement), has not yet touched any food today.

In one variant of this recollection, she simply stands there, defending herself. She wants to end the discussion on her terms. In another version (which is the more comforting, thus probably the more distorted one) she keeps attacking with fierce stabs, brandishing the fork as if it were a sword. Was it self-control that kept her from taking the knife instead? She is right-handed, after all.

Though never hitting its target, the fork, brandished or not, becomes indeed an effective weapon in this fight. It’s an immediate symbol, a sudden and unmistakable reminder that it is in her hands to refuse nourishment, to withhold the care she has been expected to provide for so many years, and to drive the overgrown child from the parental table—and out of the house.

“Get out. Now!”

She is in control and knows it. She will win this, too, even though the length of the skirmish and the vehemence of the resistance are taxing her mettle. It has been taxed plenty. In this house, coexistence has always been subject to contest, as if decisions about a game of cards, a piece of furniture moved from its usual spot, or even the distribution of a single piece of pie were fundamental matters of survival. In this house, anything could be weaponized. In this house, which since the day of its conception has been a challenge to the ideals of domesticity and concord, has slowly worn down the respect and dignity of its inhabitants, and forced its dwellers into corners of seclusion, scheming and shame, it is only plaster and mortar that keeps those walled within from hurling bricks at each other.

“I want you out of here. Now. Get out. Out.” Her terse words—intelligent missiles launched in quick succession at the climactic stage of a traumatizing blitz—penetrate instantly, successfully obliterating any doubt as to the severity of her anguish, and, second thoughts thus laid waste to, even the remotest possibility of reconciliation.

This time she really means it. She screams, screeches, and hisses, her words barely escaping her clenched teeth. It is frightening and pathetic at once, this sudden theatrical turn, an over-the-top rendition of the old generation gap standard. Yet somewhere underneath the brilliant colors of this textbook illustration of parent-child conflict and adolescent rebellion is a murky layer of something far more disquieting and unseemly—something downright oedipal.

Words, exquisitely vile, surface and come within reach but remain untransmitted, untransmissible. Addressing her in that way is a taboo too strong to be broken even in a moment of desperate savagery. Instead, the longing for revenge, for a reciprocal demonstration of the pain she, too, is capable of inflicting, will feed a thousand dreams.

Ultimately, it is fear that becomes overpowering. There is more than rage in her expression. It is manifest loathing. Two decades of motherhood have taken their toll.

At last, she slams the door. A frantic attempt to climb back inside, through the open bathroom window, fails when she, with a quick turn at the handle, erects a barrier of glass and metal.

The slippery steps leading to the front door—now away from it—feel like blocks of ice, a bitterness stinging through thin polyester dress socks. There was no time to put on shoes. This is a time to evacuate. Humiliated, cold, and terrified. Thrown out of the house.

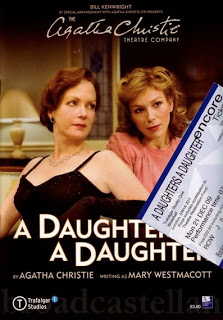

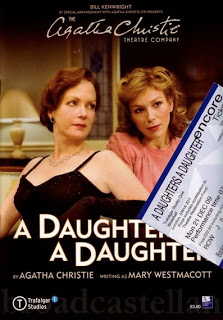

Now, contrary to what these fictionalized recollections suggest, I’m not one to cry over spilt mother’s milk; besides, I did return home—through that door—and stayed at my parents’ house for another excruciating two years. It would have been far smarter and far more dignified to let go and move on. I had clearly outstayed my welcome. The realization came to me again the other night when I went to see the A Daughter’s a Daughter, a cool examination of what may happen to close family ties once both mother and child reach maturity. The playwright, who resorted to the pseudonymous disguise of Mary Westmacott, was none other than mystery novelist Agatha Christie.

So, I oughtn’t to have been surprised by the lack of sentiment in the portrayal of a parent-child relationship that goes sour once the expiration date has passed. Think Grey Gardens without the cats. After all, in guessing games like And Then There Were None and The ABC Murders, Christie reduced human suffering to a countdown. And when she went back to the nursery, it was mainly to borrow rhymes that provided titles for some of her most memorable imaginary murders, the ruthless precision of which was a kind of voodoo doll to me during my troubled adolescence.

Still, I was surprised by the chill of the unassuming yet memorable drama acted out by Jenny Seagrove and Honeysuckle Weeks in London’s Trafalgar Studios that December evening. I was surprised by a play—staged for the first time since its weeklong run in 1956—that was not merely unsentimental but unfolded without the apparently requisite hysterics that characterize Hollywood’s traditional approaches to the subject.

To be sure, A Daughter’s a Daughter is hardly unconventional. It is not A Daughter’s a Daughter’s a Daughter. Modest rather than modernist, controlled more than contrived, it is assured and unselfconscious, a confidence to which the apparent tautology of the title attests. Yes, a daughter’s a daughter—and just what acts of filial devotion or maternal sacrifice does that entail? How far can the umbilical bond be stretched into adulthood until someone’s going to snap?

The central characters in Christie’s play reassure anyone who got away from mother or let go of a child that, whatever anyone tells you—least of all arch conservatives who urge you to trust in family because it’s cheaper than social reform—survival must mean an embrace of change and a change of embraces.

Related writings

“Istanbul (Not Constantinople); or, There’s No Boat ‘Sailing to Byzantium’”

“Caught At Last: Some Personal Notes on The Mousetrap”

“Earwitness for the Prosecution”

“On This Day in 1890 and 1934: Agatha Christie and Mutual Are Born, Ill-conceived Partnership and Issue to Follow”

“There’s no family uniting instinct, anyhow; it’s habit and sentiment and material convenience hold families together after adolescence. There’s always friction, conflict, unwilling concessions. Always!” Growing up in a familial household whose microclimate was marked by the extremes of hot-temperedness and bone-chilling calculation, I amassed enough empirical evidence to convince me that this observation—made by one of the characters in Ann Veronica (1909), H. G. Wells’s assault on Victorian conventions—is worth reconsidering. It is not enough to say that there is no “family uniting instinct.” What is likely the case during adolescence, rather than afterwards, is that the drive designed to keep us from destroying ourselves becomes the one that drives us away from each other. Depending on the test to which habit, sentiment and convenience are put, this might well constitute a family disuniting instinct.

“There’s no family uniting instinct, anyhow; it’s habit and sentiment and material convenience hold families together after adolescence. There’s always friction, conflict, unwilling concessions. Always!” Growing up in a familial household whose microclimate was marked by the extremes of hot-temperedness and bone-chilling calculation, I amassed enough empirical evidence to convince me that this observation—made by one of the characters in Ann Veronica (1909), H. G. Wells’s assault on Victorian conventions—is worth reconsidering. It is not enough to say that there is no “family uniting instinct.” What is likely the case during adolescence, rather than afterwards, is that the drive designed to keep us from destroying ourselves becomes the one that drives us away from each other. Depending on the test to which habit, sentiment and convenience are put, this might well constitute a family disuniting instinct.