Just how up have we grown since, say, the 1950s? You know, those innocent days of atomic terror, Cold War fears and anti-Communist witch-hunting. We who presume to have grown up tend to make small of what lies behind us, whether we ridicule or romanticize it. We not only know, we know better. We believe ourselves so much more educated, sophisticated or complicated than folks back in the day, whatever that day might be. It rarely occurs to us that we may have lost something other than simplicity, that we have forgotten much that was worth remembering. All those fables and fairy tales, for instance, those legends and myths that once were known to children and adults alike, the archetypal yarns that bound us, tied us to distant yet related cultures, to past generations, and to antiquity by reminding us that we are one with the earth and the universe. We have not so much grown up, it seems to me, as we are growing apart.

Just how up have we grown since, say, the 1950s? You know, those innocent days of atomic terror, Cold War fears and anti-Communist witch-hunting. We who presume to have grown up tend to make small of what lies behind us, whether we ridicule or romanticize it. We not only know, we know better. We believe ourselves so much more educated, sophisticated or complicated than folks back in the day, whatever that day might be. It rarely occurs to us that we may have lost something other than simplicity, that we have forgotten much that was worth remembering. All those fables and fairy tales, for instance, those legends and myths that once were known to children and adults alike, the archetypal yarns that bound us, tied us to distant yet related cultures, to past generations, and to antiquity by reminding us that we are one with the earth and the universe. We have not so much grown up, it seems to me, as we are growing apart.

Imagine a children’s program these days dramatizing the by now little known story of “Ceres and Prosperina,” which was heard on this day, 28 November, in 1953 by anyone tuning in to the popular and long-running radio series Let’s Pretend. Obviously, this was well before those Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles graced the plastic lunch boxes of a myth-starved generation.

Let’s Pretend rarely resorted to such faux myths and ersatz folk tales; instead, it kept many of the traditional ones alive, from “Bluebeard” to “Hiawatha,” from “Jason and the Golden Fleece” to “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Under what Norman Corwin in his Foreword to cast member Arthur Anderson’s chronicle of the program called the “benign dictatorship” of Nila Mack, Let’s Pretend “enjoyed a run of 24 years, during which it scooped up almost half a hundred national awards, and also during which the adapter-director-producer smoked two and a half packs of cigarettes daily.”

For the “Ceres and Proserpina” episode, the producers of the series (Ms. Mack, pictured above, had died earlier that year of a heart attack) did not feel obliged to explain just who these characters were, other than pointing out that this Roman myth was a perfect story for Thanksgiving, which had been celebrated two days prior to the Saturday broadcast. As the host of the series, Uncle Bill Adams, put it:

Thanksgiving is America’s own holiday; but ever since the beginning of time people have been celebrating the harvest season one way or another. The Greeks and Romans, two thousand years ago, had a wonderful harvest story. And today we’re doing it for the first time on Let’s Pretend.

All that needed to be clarified to make “Ceres and Proserpina” (as streamlined and sanitized for radio by Johanna Johnston) come alive to the target audience of tots was the meaning of the word “pomegranate.” As Sybil Trent defined it, “it’s round and red, and a little bigger than an apple, Pretenders, but the inside is full of red seeds like big currants, full of juice and very delicious.”

I suspect that, these days, the producers of a kids’ program would have to spend more time explaining or justifying their choice of presenting a myth like “Ceres and Proserpina” than they would the shape or taste of the fruit that plays such a pivotal role in it. Thanksgiving aside, the story was readily made relevant to its listeners, who were reminded of the people who, even eight years after the end of the Second World War, were living in abject poverty overseas. As announcer Jim Campbell explained:

Yes, Pretenders, now that the Thanksgiving season is almost over and everybody is beginning to think about Christmas, here’s a reminder for you to pass on to your families. Many children, and grown-ups, too, in lands that were devastated by the war, face a very miserable Christmas indeed, unless some good Americans play Santa Claus for them.

This year, a “miserable” or, at any rate, less splendid holiday season is being forecast for many families, including “some good Americans”; but no one seems to advocate Ovid’s Metamorphoses as an alternative to the computerized fantasy games that are less likely this season to fly off the shelves of the electronic stores not yet closed down for good. Along with cost-effective radio dramatics, mythology is the kind of nutritious snack that has long disappeared from the menu of children’s entertainment. The change of seasons, fancifully explained by “Ceres and Proserpine,” is now defined by commerce, by what is and what is not on display in the shop windows. It is the modern myth of perpetual growth and prosperity that may well prove the less relevant and enduring one. By all means, have that pomegranate, but brace yourself for a prolonged visit with Pluto.

However disheartening California’s majority rule in favor of amending the state constitution so as to protect an institution for which millions of divorced Americans have shown little respect, 5 November 2008 is still a day to inspire confidence in a democracy’s ability to refine and redefine itself, to let go of old prejudices so often upheld as time-honored traditions. To update and appropriate On a Note of Triumph, Norman Corwin’s cautiously optimistic radio play in commemoration of VE Day: “Seems like free men [and women] have done it again!” Perhaps, it seems even more of a victory to those living in Europe and elsewhere around the world.

However disheartening California’s majority rule in favor of amending the state constitution so as to protect an institution for which millions of divorced Americans have shown little respect, 5 November 2008 is still a day to inspire confidence in a democracy’s ability to refine and redefine itself, to let go of old prejudices so often upheld as time-honored traditions. To update and appropriate On a Note of Triumph, Norman Corwin’s cautiously optimistic radio play in commemoration of VE Day: “Seems like free men [and women] have done it again!” Perhaps, it seems even more of a victory to those living in Europe and elsewhere around the world.

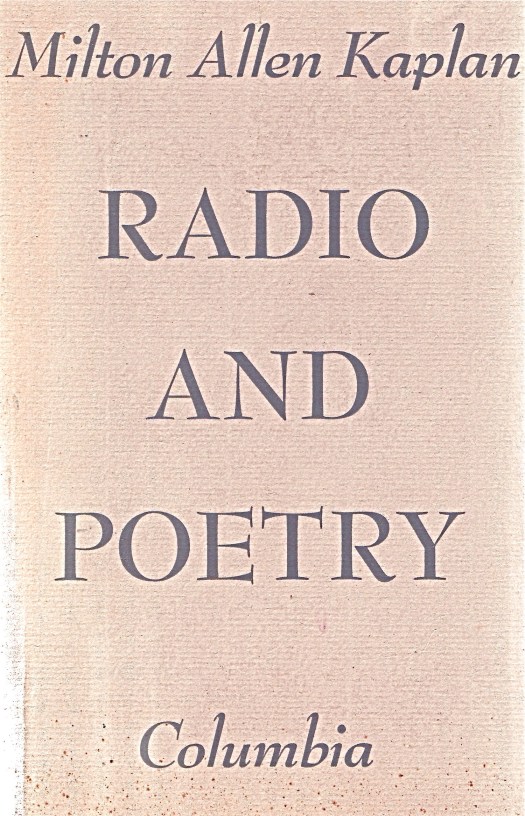

Well, it kept Bing Crosby on the air; but it also made that air feel a lot staler. Magnetic tape. Its introduction back in 1946 was a recorded death sentence to the miracle and the madness of live radio. Dreaded by producers of minutely timed dramas and comedy programs, going live had been the life or radio. Intimate and immediate, each half-hour behind the microphone had the urgency of a once-in-a-lifetime event. Actors and musicians gathered for a special moment and remained in the presence of the listener for the express purpose of being there for them and with them, however far away. They made time for an audience that, in turn, was making time for them. In a world of commerce in which democratic principles were reduced to the ready access to cheap reproductions, the quality of being inimitable and original was fast becoming a rare commodity indeed. The time for the magic of the time-bound art, the theater of the fourth dimension, was fast running out.

Well, it kept Bing Crosby on the air; but it also made that air feel a lot staler. Magnetic tape. Its introduction back in 1946 was a recorded death sentence to the miracle and the madness of live radio. Dreaded by producers of minutely timed dramas and comedy programs, going live had been the life or radio. Intimate and immediate, each half-hour behind the microphone had the urgency of a once-in-a-lifetime event. Actors and musicians gathered for a special moment and remained in the presence of the listener for the express purpose of being there for them and with them, however far away. They made time for an audience that, in turn, was making time for them. In a world of commerce in which democratic principles were reduced to the ready access to cheap reproductions, the quality of being inimitable and original was fast becoming a rare commodity indeed. The time for the magic of the time-bound art, the theater of the fourth dimension, was fast running out. Well, it wasn’t exactly business as usual on this day, 7 December, back in 1941. Mind you, lucre-minded broadcasters tried hard to keep the well-oiled machinery of commercial radio running. There were soap operas and there was popular music, interrupted in a fashion rehearsed by “The War of the Worlds,” by updates about the developments of the attack on Pearl Harbor (

Well, it wasn’t exactly business as usual on this day, 7 December, back in 1941. Mind you, lucre-minded broadcasters tried hard to keep the well-oiled machinery of commercial radio running. There were soap operas and there was popular music, interrupted in a fashion rehearsed by “The War of the Worlds,” by updates about the developments of the attack on Pearl Harbor ( Just where did it go—or go wrong—he wonders, as he passes the could-be-anywhere shopping complex to wend his way back after a Mexican meal and a surprisingly good Long Island Iced Tea to the

Just where did it go—or go wrong—he wonders, as he passes the could-be-anywhere shopping complex to wend his way back after a Mexican meal and a surprisingly good Long Island Iced Tea to the