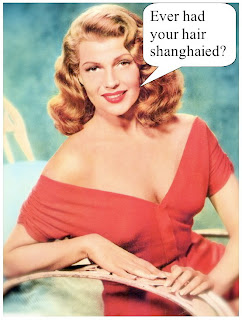

Well, my head’s still spinning from last night’s screening of The Lady from Shanghai. You know, that fascinating, pieced together puzzler for the making of which star and director Orson Welles decided to give his celebrated redhead wife Rita Hayworth the old peroxide treatment and turn her Lana. Now, I got lost somewhere in the cross-and-double-cross scenario; but even before the plot unravelled and ultimately revelled in its fun house mirroring of noirish nightmares, my willingness to go along for the ride got deflected by the film’s opening scenes. Although I had never before watched this picture in what now goes for its entirety, l sensed that I had come across it (or something rather like it) before. Trust me, “Where does The Lady from Shanghai come from?” isn’t meant to be one of those “Who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb” questions.

Well, my head’s still spinning from last night’s screening of The Lady from Shanghai. You know, that fascinating, pieced together puzzler for the making of which star and director Orson Welles decided to give his celebrated redhead wife Rita Hayworth the old peroxide treatment and turn her Lana. Now, I got lost somewhere in the cross-and-double-cross scenario; but even before the plot unravelled and ultimately revelled in its fun house mirroring of noirish nightmares, my willingness to go along for the ride got deflected by the film’s opening scenes. Although I had never before watched this picture in what now goes for its entirety, l sensed that I had come across it (or something rather like it) before. Trust me, “Where does The Lady from Shanghai come from?” isn’t meant to be one of those “Who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb” questions.

Welles is known to have borrowed ideas, narrative devices and storylines, from his radio programs and recycled or reworked them for his motion pictures and stage productions. Examples of these trans-mediations are the 1938 Mercury Theater productions of “A Heart of Darkness” (which Welles had hoped to adapt for the movies) and “Around the World in Eighty Days” (with a musical version of which he belly-flopped on Broadway in the late spring of 1946), as well as the 1939 Campbell Playhouse revisitation of the William Archer’s 1921 melodrama The Green Goddess (with which he toured some six months after its initial radio broadcast). Based on the novel If I Die Before I Wake by one Sherwood King, a book that Welles initially did not bother to read, the troubled Lady might very well might have some roots in radio.

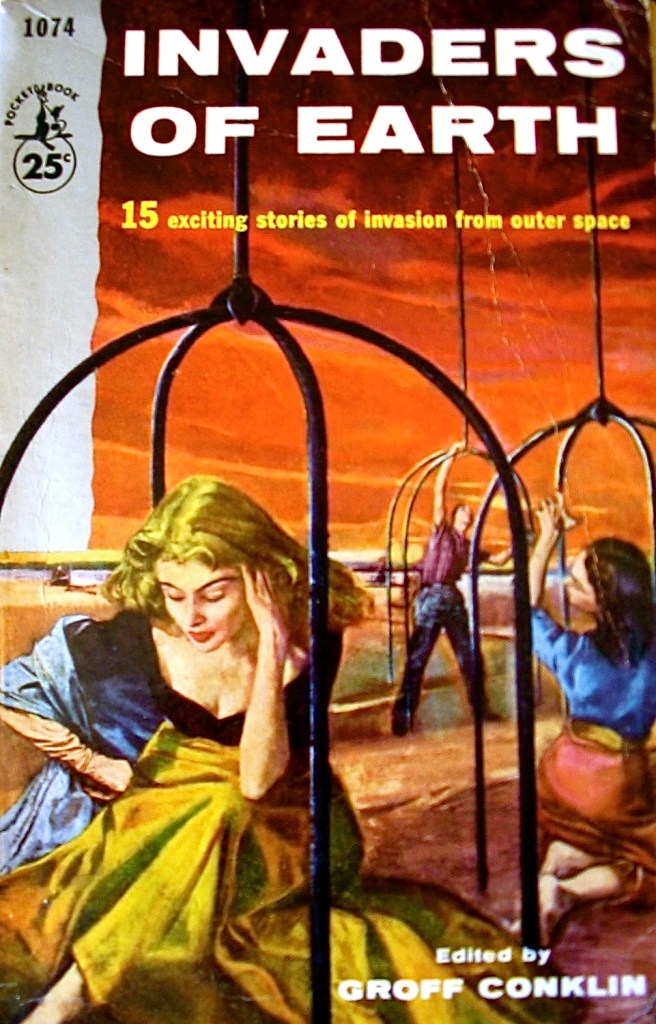

At any rate, The Lady brought to mind the 15 October 1939 Campbell Playhouse update of John Galsworthy’s Escape (1926). Both Lady and “Escape” are initially set in Manhattan and tell the story of a man (played by Welles) who finds himself in Central Park after dark and in trouble thereafter. Both men ride around in that most romantic and impractical means of urban transportation, the horse-drawn carriage, and encounter a seductress whom only the most chivalrous nature would take for a damsel in distress. In each case, the hero comes to the aid of the questionable dame, and thereby implicates himself as he, in the Thirty-Nine Steps tradition of botched heroics, is caught and tried for a violent crime. While on the run from the law, both men manage to extract themselves and set things right at last.

So, just where does The Lady from Shanghai come from? Aside from tracing her origins to the melodramatic tradition—and a mind like mine that is steeped in it—I do not presume to have a conclusive answer. In Welles and Mercury Player Everett Sloane, The Lady has several tangible connections to the world of the wireless, another link being Fletcher Markle, a radio playwright who had a hand in reshaping the material. Approaching this sordid portrait of a The Lady while under the influence of countless pieces of fiction, I cannot help but draw such parallels; getting carried away in my own speculations, I am being drawn in and out of the pictures I thus reframe.

My pursuit having taken me to the Internet Movie Database, I discovered that I am not alone one who’s reframing The Lady these days. After receiving more ill-advised nips, tucks and facelifts than Cher and Joan Rivers combined, The Lady from Shanghai is now being readied for a radical makeover. According to the Internet Movie Database, the titular dame will soon assume the likeness of altogether un-Hayworthy Rachel Weizs, whose transformation into a femme fatale would require more than the services of a daring hairstylist. Thus, another iconic film is being shanghaied by the new and far from improved Hollywood.

Well, I consume plenty of them. Movies, I mean. Almost every night I take one in, along with some potato chips and a tall glass of gin and tonic. Now, looking in the mirror, I pretty much know where the chips and the gin are going, being that the residue lingers prominently around my waste. I don’t mind that much. I’m talking celluloid, not cellulite.

Well, I consume plenty of them. Movies, I mean. Almost every night I take one in, along with some potato chips and a tall glass of gin and tonic. Now, looking in the mirror, I pretty much know where the chips and the gin are going, being that the residue lingers prominently around my waste. I don’t mind that much. I’m talking celluloid, not cellulite. The afternoon couldn’t be any less gloomy. The sky is of a deep blue, the air is fresh, and—until the health hazard that is Tony Blair gets his death wish to turn the West of Britain

The afternoon couldn’t be any less gloomy. The sky is of a deep blue, the air is fresh, and—until the health hazard that is Tony Blair gets his death wish to turn the West of Britain I had intended to spend much of today al fresco, our long-neglected garden being in serious need of attention. Dragging the old lawnmower out of hibernal retirement a while ago, I had managed to knock over a can of paint and, the spilled contents being blue, very nearly ended up looking like a Smurf in the process. No sooner had we unleashed the noisy monstrosity, engulfed in a cloud of smoke, than one of its wheels broke off, which immediately put a stop to my horticultural endeavors. It is to the latter mishap on this Not-So-Good Friday and the fact that I am all thumbs (none of which green) that you owe the questionable pleasure of this entry in the broadcastellan journal.

I had intended to spend much of today al fresco, our long-neglected garden being in serious need of attention. Dragging the old lawnmower out of hibernal retirement a while ago, I had managed to knock over a can of paint and, the spilled contents being blue, very nearly ended up looking like a Smurf in the process. No sooner had we unleashed the noisy monstrosity, engulfed in a cloud of smoke, than one of its wheels broke off, which immediately put a stop to my horticultural endeavors. It is to the latter mishap on this Not-So-Good Friday and the fact that I am all thumbs (none of which green) that you owe the questionable pleasure of this entry in the broadcastellan journal. Last night, I watched The Red Dragon (1945), another one in the long-running series of Charlie Chan movies. To my surprise, there was a familiar voice in the cast: Barton Yarborough, one of the three comrades of the I Love a Mystery radio serial I’m going to review, starting tomorrow. On the radio, Yarborough’s Texan drawl was taking center stage, and, “honest to grandma,” I’ll sure enjoy hearing it again in the weeks to come. Before I get started, however, I need to acknowledge the anniversary of what is unquestionably the most famous of American radio plays, the Mercury Theatre production of “The War of the Worlds.”

Last night, I watched The Red Dragon (1945), another one in the long-running series of Charlie Chan movies. To my surprise, there was a familiar voice in the cast: Barton Yarborough, one of the three comrades of the I Love a Mystery radio serial I’m going to review, starting tomorrow. On the radio, Yarborough’s Texan drawl was taking center stage, and, “honest to grandma,” I’ll sure enjoy hearing it again in the weeks to come. Before I get started, however, I need to acknowledge the anniversary of what is unquestionably the most famous of American radio plays, the Mercury Theatre production of “The War of the Worlds.”

I remember the first time I heard the menacing voice of The Shadow—and it was not over the radio. I was a college student in New York City and was cleaning the Upper East Side apartment of a fading southern belle. Well, I needed the cash and she was too much of

I remember the first time I heard the menacing voice of The Shadow—and it was not over the radio. I was a college student in New York City and was cleaning the Upper East Side apartment of a fading southern belle. Well, I needed the cash and she was too much of