“Amos ‘n’ Andy is old-fashioned,” radio critic Darwin L. Teilhet complained as early as 1932. “Its dramatic machinery creaks.” He much preferred Myrt and Marge, a 42nd Street-smart if way-off-Broadway Melody then in its inaugural season. To Teilhet, Myrt and Marge was not only “very good serialized melodrama,” it was the “most advanced program of its type now on the air.”

For all its popularity—and its groundbreaking granddaddy-of-them-all status—Amos ‘n’ Andy sure was “old-fashioned.” Indeed, its success depended on that comforting, reassuring recognizability—comforting and reassuring, that is, to folks who thought a black face routine less troubling than the effectuation of racial equality. The early 1930s were highly competitive times of economic hardship, and to hear potential competitors bumbling and make fools of themselves must have been comic relief to the paler faces in the crowd, the faces that mattered most to sponsors.

So, how fresh-faced were Myrt and Marge by comparison? And why was it that, by January 1933, their serialized adventures came pretty close to rivaling Amos ‘n’ Andy in the ratings? Never having been enthusiastic about the latter, I was eager to find out.

As next to nothing is left of the program’s initial run, I had to take the critics’ ear and word for the “it” of listening. Teilhet, for one, was wowed by the “swift lines,” which he found to be “very different from Amos’ and Andy’s ponderous exchanges.”

Indeed, those “swift lines” translated into swell curves in the critic’s mind. “Miss [Donna] Damerel [as Marge] provides a sweet and pure sex interest,” Teilhet opined, “which can be safely gulped down by the hinterland without making the children go to bed before their proper hour.” It took an adult’s imagination of adulterated purity to figure that not all that occurred in the lives of chorines Myrt and Marge was altogether “sweet and pure,” least of all by the puritan standards commercial radio was obliged to uphold.

According to Teilhet, the “tempo” set by the two leads was “hard and glittering.” Myrt and Marge was quick to respond to the public’s fascination with Al Capone and Little Caesar by turning the backstage drama into an “exciting gangster story.” It brought a touch of Dillinger to the dilly-dalliance of romantic serials, then still a genre in search of a formula. By doing so, and by implicating its leads, Myrt and Marge came as close to pre-code Hollywood as network radio could get.

What’s more, Teilhet remarked, that “tempo” was “directly traceable to the vaudeville antecedents” of Myrtle Vail, who created the serial, wrote and starred in it. “The things she has seen—and experienced,” winked Radio Guide’s Arthur Kent in 1934. Kent attributed the program’s success to the fact that the title characters were played by actresses who were mother and daughter in real life and that Myrtle Vail had “lived in three great epochs of show business: epochs dominated, respectively, by stage, movies and radio.” Having “been though it all,” Vail now wrote “the life of the theater as well as her own life into her script.” Like a true trouper, she carried on even after the death of her co-starring daughter in 1941.

At least on one occasion, the realism was inspired by actual events. “That tearful episode of Myrt and Marge last week was not the result of an emotionally successful script, m’dears,” readers of Radio Guide’s issue for the week ending 1 February 1936 were told. “No, it was because the cast almost was overcome by tear gas fumes released when the bank adjoining the CBS studios tested out its automatic vault system.”

I am surprised that listeners, if not overcome by the vapors, weren’t positively fuming at some of the backstage goings-on. Perhaps they were overcome, which may account for the lack of documented complaints, radio’s chief tool of self-censoring. Could they have been oblivious of the program’s other or third “sex interest”—that flaming figure in the dressing room?

What Myrt and Marge brought into American homes, if they didn’t already have one in the closet—and what contributed to renewed interest in the serial, albeit as a mere pop-cultural footnote—was Clarence Tiffingtuffer, the queer sidekick responsible for the gowns worn by the show-busy leads, and for considerable gossip besides.

If listeners were clueless, the hoofers sure weren’t. When teenager Marge, the newest member of Hayfield Pleasures celebrated precision chorus, feels uncomfortable about being fitted by a man, one of her fellow chorines hisses “Don’t worry, he’ll never harm a hair o’ your head, dearie.” Rather than being the brunt of it, Clarence dishes out some “swift lines” of his own. “Those gams of yours are practically parenthetical,” he remarks upon the alleged assets in his sartorial care.

Now, belated followers of Myrt and Marge have to make do with a mid-to-late 1940s revival of the serial (although a 1933 film version featuring the radio cast is extant). Gone are the true-to-life leads; gone, too, is much of what had seemed “different” or “advanced” about the serial back in 1932. Yet even though we now have to settle for Myrt and Marge-arine, the substitute still retains a flavor of the first outing, as the actor originating the part of Clarence, Ray Hedge, reprises the role he made his own.

I can imagine that, had I been growing up in the early 1930s, Myrt and Marge would have made me feel a little less marginal by moving someone recognizably like me—yet way out there, enjoying a career and a life of make-believe—into the center of the action. How thrilling it would have been to hear Myrt and Marge take to the soundstage set by their better-known seniors, Gosden and Correll, and listen to them tear down that old minstrel show-on-taxi cab wheels. With Clarence in their midst, and on my mind, it sure would have sounded like the “most advanced program of its type.”

To be continued, as they say in soap opera land.

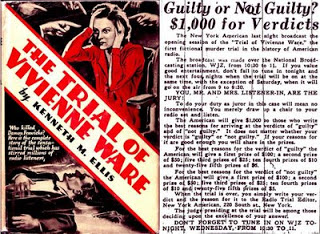

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

Well, I am back from my three-day getaway to Manchester, my makeshift Manhattan. And what a poor substitute it has proven once again. The only bright spot of an otherwise less than scintillating weekend was the production of James M. Barrie’s comedy What Every Woman Knows at the

Well, I am back from my three-day getaway to Manchester, my makeshift Manhattan. And what a poor substitute it has proven once again. The only bright spot of an otherwise less than scintillating weekend was the production of James M. Barrie’s comedy What Every Woman Knows at the