How many times have I said to myself, “Wake up and hear the tulips”? Literally, never. But the improbability of following such a directive has crossed my mind, especially during the pandemic that has kept us from venturing out into the world and fully to engage all of our senses. Seeing images of flowers is hardly the same thing as experiencing spring.

The limitations of vicarious living online have made themselves felt. I, for one, am not feeling it anymore, this ersatz world of keeping in touch without touching, of being nosey without the chance of a whiff, of getting a taste of what it’s like out there without getting as much as a morsel of it inside me.

That said, here I am online, flicking through digitized magazines and newspapers of yesteryear, a forest of ancient pulp springing back to life for a belated flowering. Searching for nothing in particular, I came across this headline in an edition of Radio Dial dating from 20 May 1937: “Ted Husing to Describe Tulip Festival.” Is there anything less phonogenic than an oversized still life of flowers?

More incongruous than the idea of devoting a sound-only broadcast to such a spectacle is the choice of Ted Husing as the guy to try out his ekphrastic skills on it. Was not Husing a celebrated sportscaster, typecast as such in movies like To Please a Lady (1950), as I mentioned here a long while back? It must have been challenging for him to get animated when tasked with the assignment of making Liliaceae sound lively through verbal acrobatics. I’m guessing. I never heard the broadcast.

‘Actually,’ sports were only one aspect of his career in radio. Husing remarked in retrospect that he ‘logged far more broadcasting time on music and special events.’ He claimed to have been responsible for the discovery or promotion of entertainers including Rudy Vallee, Guy Lombardo, Bing Crosby, and Desi Arnaz.

Husing had a nose for radio’s no-show business, all right. In fact, he had it broken for that very purpose, as he explained it in his first autobiography, Ten Years Before the Mike (1935):

Some of the acoustics experts and sinus engineers decided my voice would have a bit more resonance if my antrums were widened. Or is it antra? Anyhow, since the technical people had spent years perfecting microphones especially for my vocal vibrations, I couldn’t see how I could hold back on my antrums, personal as they are to me. So I went to the sawbones, took a couple of shots of coke, and had ’em broken out.

Having gone through such lengths, you might as well travel to Holland to tell folks at home what tulips look like. In fact, Husing only went as far as Holland, Michigan, where the festival in question was held annually. And it wasn’t all about the tulips, either, as tiptoers were given a run for their money by the ‘Klompen Dance,’ an orchestrated clacking of thousands of wooden shoes on the pavement. The article also threatened folk songs. Not much demand for subtle word-painting there.

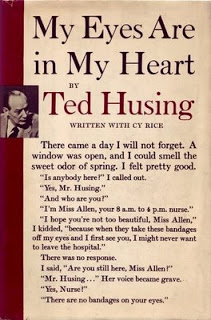

Antrum, tantrum. However he felt that day, Husing was lucky to have had assignments like this, to have spent years translating observed sights into spoken words. Lucky, because he ended up losing his eyesight after a brain tumor operation. I imagine that spending much of his life on the air, creating a world made of sound helped him to shape a life for himself that was focused on the vision he only partially recovered.

Sure, radio is a sound-only medium; but it encourages the translative act of hearing that opens us up to the senses that we might lose sight of if we rely too much on our eyes. No need to cue those Klompen Dancers to drive the point home.

Sometimes, when my heart is not in in, my mind’s eye begins to stray. That was what happened a while back when I tried To Please a Lady. Tried to follow it, that is. The Lady in question is one of Barbara Stanwyck’s decidedly lesser vehicles, and the horsepower on display in it is not likely to get my heart a-racing. Still,

Sometimes, when my heart is not in in, my mind’s eye begins to stray. That was what happened a while back when I tried To Please a Lady. Tried to follow it, that is. The Lady in question is one of Barbara Stanwyck’s decidedly lesser vehicles, and the horsepower on display in it is not likely to get my heart a-racing. Still,

She played tougher than anyone else in pictures, and she was better at it. She could get a guy to fall for her and a fall guy to do anything for her, be it to lie, cheat, or kill. To please her was a dangerous game; but to displease her was a deadly one. She could make puppets of men;

She played tougher than anyone else in pictures, and she was better at it. She could get a guy to fall for her and a fall guy to do anything for her, be it to lie, cheat, or kill. To please her was a dangerous game; but to displease her was a deadly one. She could make puppets of men;