I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

With those words, capturing her first impression and anticipation of a “strange land” as, on 15 March 1862, it came into partial view—the “outlook” being “blinded”—aboard the steamer Chow Phya, Anna Harriette Leonowens commenced The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870), the “Recollections of Six Years in the Royal Palace at Bangkok.” The account of her experience was to be followed up by a sensational sequel, Romance of the Harem (1872), both of which volumes became the source for a bestselling novel, Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam (1944), several film and television adaptations, as well as the enduringly crowd-pleasing musical The King and I.

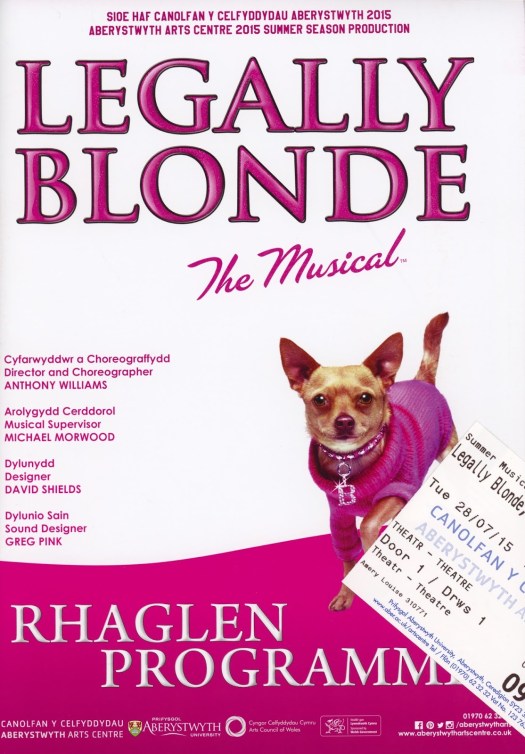

Conceived for musical comedy star Gertrude Lawrence, the titular “I” is currently impersonated by Shona Lindsay, who, until the end of August 2009, stars in the handsomely designed Aberystwyth Arts Centre Summer Musical Production of the Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic.

The title of the musical personalizes the story, at once suggesting authenticity and acknowledging bias. Just as it was meant to signal the true star of the original production—until Yul Brynner stole the show—it seems to fix the perspective, assuming that we, the audience, see Siam and read its ruler through Anna’s eyes. And yet, what makes The King and I something truly wonderful—and rather more complex than a one-sided missionary’s tale—is that we get to know and understand not only the Western governess, but the proud “Lord and Master” and his daring slave Tuptim.

Instead of accepting Anna as model or guide, we can all become the “I” in this story of identity, otherness and oppression. Tuptim’s experience, in particular, resonates with anyone who, like myself, has ever been compelled, metaphorically speaking, to “kiss in a shadow,” to love without enjoying equality or protection under the law. Tuptim’s readily translatable story, which has been rejected as fictive and insensitive, is emotionally rather than culturally true.

“Truth is often stranger than fiction,” Leonowens remarked in her preface to Romance of the Harem, insisting on the veracity of her account. Truth is, truth is no stranger to fiction. All history is narrative and, as such, fiction—that is, it is made up, however authentic the fabric, and woven into logical and intelligible patterns. Whoever determines or imposes such patterns—the historian, the novelist, the reporter—is responsible for selecting, evaluating, and shaping a story that, in turn, is capable of shaping us.

Tuptim’s adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which strikes us at first strange and laughable—then uncanny and eerily interchangeable—in its inauthentic, allegorical retelling of a fiction that not only made but changed history, is an explanation of and validation for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s sentimental formula. Through the estrangement from the historically and culturally familiar, strange characters become familiar to us, just Leonowens may have been aided rather than mislead by an “outlook” that was “blinded” by the intimate knowledge of a child’s love.

Strange it was, then, to have historicity or nationality thrust upon me as Anna exclaims, in her undelivered speech to the King, that she hails “from a civilized land called Wales.” It was a claim made by Leonowens herself and propagated in accounts like Mrs. Leonowens by John MacNaughton (1915); yet, according to Susan Brown’s “Alternatives to the Missionary Position: Anna Leonowens as Victorian Travel Writer” (1995), “no evidence supports” the assertion that Leonowens was raised or educated in Wales.

Still, there was an audible if politely subdued cheer in the Aberystwyth Arts Centre auditorium as Anna revealed her fictive origins to us. Granted, I may be more suspicious of nationalism than I am of globalization; but to define Leonowens’s experience with and derive a sense of identity from a single—and rather ironic reference to home—seems strangely out of place, considering that the play encourages us to examine ourselves in the reflection or refraction of another culture, however counterfeit or vague. Beside, unlike last year’s miscast Eliza (in the Arts Centre’s production of My Fair Lady), Anna, as interpreted by Ms. Lindsay, has no trace of a Welsh accent.

As readers and theatergoers, we have been “getting to know you,” Anna Leonowens, for nearly one and a half centuries now; but the various (auto)biographical accounts are so inconclusive and diverging that it seems futile to insist on “getting to know all about you,” no matter now much the quest for verifiable truths might be our “cup of tea.” What is a “puzzlement” to the historians is also the key to the musical, mythical kingdom, an understood realm in which understanding lies beyond the finite boundaries of the factual.

Related writings

“By [David], she’s got it”; or, To Be Fair About the Lady

Delayed Exposure: A Man, a Monument, and a Musical

Related recordings

“Meet Gertrude Lawrence,” Biography in Sound (23 January 1955)

Hear It Now (25 May 1951), which includes recorded auditions for the role of Prince Chulalongkorn in The King and I

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.