In “‘Hawkers of feces? Costermongers of shit?’: Exits and Recantations,” the final chapter of Immaterial Culture, I briefly discuss how creative talent working in the US broadcasting industry during the 1930s and 1940s tended to recall their experience upon closing the door to the world of radio in order to pursue careers they deemed more lofty and worthy. Few had anything positive to say about that world, and their reminiscences range from ridicule to vitriol.

Within a year or two after the end of the Second World War, attacks on the radio industry became widespread and popular; most notable among them was The Hucksters, a novel by Frederic Wakeman, a former employee of the advertising agency Lord & Thomas. Between 1937 and 1945, Wakeman had developed radio programs and sales campaigns for corporate sponsors, an experience that apparently convinced him to conclude there was ‘no need to caricature radio. All you have to do,’ the author’s fictional spokesperson sneers, ‘is listen to it.’

Such ‘parting shots,’ as I call them in Immaterial Culture, resonated with an audience that, after years of fighting and home front sacrifices, found it sobering that Democratic ideals, the Four Freedoms and the Pursuit of Happiness were being reduced to the right – and duty – to consume. After a period of relative restraint, post-war radio went all out to spread such a message, until television took over and made that message stick with pictures showing the latest goods to get and guard against Communism.

Following – and no doubt encouraged by – the commercial success of The Hucksters, the soap opera writer Robert Hardy Andrews published Legend of a Lady, a novel set, like Wakeman’s fictional exposé, in the world of advertising. Andrews probably calculated that like The Hucksters and owing to it Legend would be adapted for the screen, as his novel Windfall had been.

Unlike in The Hucksters, the industry setting is secondary in Legend of a Lady. Andrews has less to say about radio than he has about women in the workforce. And what he has to say on that subject the dust jacket duly proclaims: ‘Legend of a Lady is the story of pretty, fragile Rita Martin, who beneath her charming exterior is hell-bent for personal success and who tramples with small, well-shod feet on all who stand in her way.’ The publisher insisted that ‘it would be hard to find a more interesting and appalling character.’

I did not read the blurb beforehand, and, knowing little about the novel other than the milieu in which it is set, I was not quite prepared for the treatment the title character receives not only by the men around her but by the author. The Legend of the Lady, which I finished reading yesterday, thinking it might be just the stuff for a reboot of my blog, opens intriguingly, and with cinematic potential, as the Lady in question picks up ‘her famous white-enameled portable typewriter in small but strong hands’ and throws it ‘through the glass in the office widow,’ right down onto Madison Avenue, the artificial heart of the advertising industry.

This is Mad Women, I thought, and looked forward to learning, in flashback, how a ‘small but strong’ female executive gets to weaponise a tool of the trade instead of dutifully sitting in front of it like so many stereotypical office gals. Legend of a Lady is ‘appalling’ indeed, reminding readers that dangerous women may be deceptively diminutive, that they are after the jobs held by their male counterparts, and that, rest assured, dear conservative reader, they will pay for it. In the end, Rita Martin, a single mother trying to gain independence from her husband and making a living during the Great Depression, exists an office ‘she would never enter again.’ Along the way, she loses everything –spoiler alert – from her sanity to her son.

The blurb promises fireworks, but what Legend of a Lady delivers is arson. It is intent on reducing to ashes the aspirational ‘legend’ of women who aim to control their destiny in post-war America. The world of soap opera writing and production serves as mere a backdrop to render such ambitions all the more misguided: soap operas are no more real than the claim that working for them is a meaningful goal. As a writer of serials for mass consumption, Robert Hardy Andrews apparently felt threatened and emasculated working in a business in which women achieved some success in executive roles. In a fiction in which men big and small suffer deaths and fates worth than that at the delicate hand of Rita Martin, Andrews created for himself a neo-romantic alter ego – the rude, nonchalant freelance writer Tay Crofton, who refuses to be dominated by a woman he would like to claim for himself but does not accept as a partner on her own terms, presumably because she cannot be entrusted with the power she succeeds in wresting from the men around her without as much as raising her voice.

Devoid of the trimmings and trappings of Hollywood storytelling, without glamor or camp, without gowns by Adrian or brows by Crawford, Legend of a Lady serves its misogyny straight up – but it couches its caution against ‘small’ women in spurious philosophy by claiming that, for men and women alike, there is life outside the proverbial squirrel cage that Andrews relentlessly rattles for his agonizing spin on the battle of the sexes.

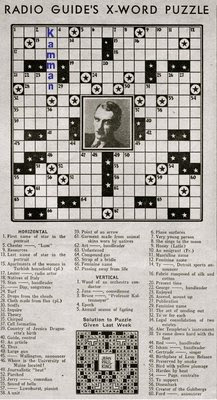

I am one of those forward-looking folks who peruse the television and radio listings as if they were stock market reports or racing forms. Determined not to miss a winner of a program, I prepare myself by wielding the ever ready text marker as I wend my way through the weekly offerings. Today, though, I am seriously late in my planning. Before me is the US broadcast schedule from 4 January 1942 as it appeared in an issue of the Radio-Movie Mirror.

I am one of those forward-looking folks who peruse the television and radio listings as if they were stock market reports or racing forms. Determined not to miss a winner of a program, I prepare myself by wielding the ever ready text marker as I wend my way through the weekly offerings. Today, though, I am seriously late in my planning. Before me is the US broadcast schedule from 4 January 1942 as it appeared in an issue of the Radio-Movie Mirror.  Well, it took me some time to get it. Thanksgiving, I mean. Being German, I was unaccustomed to the holiday when I moved to the United States in the early 1990s. I didn’t quite understand what Steve Martin’s character in Trains, Planes & Automobiles was so desperately rushing home to . . . until I had lived long enough on American soil to sense the significance of this day. Now that I am living in Britain and, unlike last year, not flying back to America to observe it, I wish I could import the tradition.

Well, it took me some time to get it. Thanksgiving, I mean. Being German, I was unaccustomed to the holiday when I moved to the United States in the early 1990s. I didn’t quite understand what Steve Martin’s character in Trains, Planes & Automobiles was so desperately rushing home to . . . until I had lived long enough on American soil to sense the significance of this day. Now that I am living in Britain and, unlike last year, not flying back to America to observe it, I wish I could import the tradition.

Well, I hadn’t intended to continue quite so sporadic in my out-of-date updates, especially since a visit to my old neighborhood in New York City is likely to bring about further disruptions in the weeks to come, however welcome the cause itself might be. A series of brief power outages last Friday and my subsequent haphazard tinkering with our faltering wireless network are behind my most recent disappearance. It is owing to the know-how of

Well, I hadn’t intended to continue quite so sporadic in my out-of-date updates, especially since a visit to my old neighborhood in New York City is likely to bring about further disruptions in the weeks to come, however welcome the cause itself might be. A series of brief power outages last Friday and my subsequent haphazard tinkering with our faltering wireless network are behind my most recent disappearance. It is owing to the know-how of