When I was growing up, looking forward to Christmas meant opening the Türchen (little doors) of an advent calendar (last shown here). Every morning, for twenty-four days, colorful pictures marked the countdown to Heiligabend, as Christmas Eve is known and celebrated in my native Germany. In an update of this seeming oxymoron—the surprise-filled ritual—I am trying to turn this journal into such a calendar, discovering something new to think, wonder, and write about. There won’t be twenty-four doors, mind you, since I am going to make an exit to London on the 17th, from which day forward there will be many a silent night here at broadcastellan; but, during the next few weeks, I shall open as many Türchen as time and internet access permit.

When I was growing up, looking forward to Christmas meant opening the Türchen (little doors) of an advent calendar (last shown here). Every morning, for twenty-four days, colorful pictures marked the countdown to Heiligabend, as Christmas Eve is known and celebrated in my native Germany. In an update of this seeming oxymoron—the surprise-filled ritual—I am trying to turn this journal into such a calendar, discovering something new to think, wonder, and write about. There won’t be twenty-four doors, mind you, since I am going to make an exit to London on the 17th, from which day forward there will be many a silent night here at broadcastellan; but, during the next few weeks, I shall open as many Türchen as time and internet access permit.

Perhaps, this isn’t so very different from what I do with this journal throughout the year; but I shall endeavor to make what’s behind the door a revelation, or a surprise, at least, to myself—stories, voices, and personalities I have not yet mentioned on these virtual pages. Rather than being a reflex, the surprise is a reaction for which I shall have to strive. What I find behind those closed doors, I should add, may not always befit the spirit of the season.

I shall open the first door by picking up The Magic Key, a popular US radio variety program of the mid to late 1930s; sponsored by RCA, it was designed to promote the wonders of radio, no expenses spared. On this day, 1 December, in 1935, the hourlong program offered “varied entertainment, from Buenos Aires, Ottawa, Canada, Chicago and New York City, presented for the families of the nation by the members of the family of RCA.”

The afternoon’s entertainers included silent screen idol Richard Barthelmess who, opposite Warner Brothers’ star Jean Muir, made “one of his rare microphone appearances” in a scene from Maxwell Anderson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Saturday’s Children, along with Eddy Duchin and his orchestra, Eduardo Donato and his tango ensemble, members of the cast of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and, if that weren’t varied entertainment enough, John B. Kennedy touring the Chicago stockyards and a report from Canada’s Minister of Agriculture. All live, of course, both from the studio and via hook-ups.

The Magic Key was a marvel in this respect, and it wasn’t bashful about being marvelous: “Within the memory of men now living, the speediest communication between New York and Buenos Aires consumed twenty-seven days. Today, we’ll make the journey in so many seconds [. . .].”

The highlight, for me, are the scenes from Saturday’s Children; but it is difficult to enjoy the performance, knowing what actress Jean Muir had to endure throughout the 1950s, when the doors to sound stages and broadcast studios were closed to her as a direct result of anti-Communist hysteria. In 1950, Muir’s name appeared in Red Channels, effectively barring her from starring in the television version of The Aldrich Family. As Rita Morley Harvey tells it in Those Wonderful, Terrible Years, Muir sought “solace” in alcohol, suffering “poor health” and “personal sorrow.”

Muir’s is a notorious case of witch-hunting; and, considering that few recordings of her radio performances are extant today, it is a thrill to hear her on this Magic Key program, well before radio, anxious to avoid scandal and diminished returns, decided to lock her out. “The proverb says,” Richard Barthelmess remarked in an overly complicated setting of the scene, “that Saturday’s children must work for a living”; but a regular job as only radio and motion pictures could offer an actor back then was a luxury denied the talented Ms. Muir.

As if to comment on things to come, the scenes from Anderson’s play involve a peculiar gift: a bolt, a hammer, and a screwdriver, given to Muir’s character, “a free agent” lately separated from her husband, by her boss, an admirer who wanted to guard against an inquisitive landlady. “Anytime you want a bolt on your door,” her still-loving husband implores her, “I wish you’d ask me.” Unlike Muir, her character got to choose whether to bolt the door or bolt.

The broadcast closes with the obligatory holiday shopping reminder, announcer Milton Cross insisting that the “members of the family of RCA [were] eager to help make your Christmas holidays happy ones. Will there be an RCA Victor in your home this Christmas?” I wish there were occasion for such a purchase these days; but, about half a century ago, the makers and sponsors of radio entertainment decided to throw away those magic keys to the kingdom of make-believe . . .

“The importance of the ‘word’ was lost when television took over the living rooms of America. Sure, there were plenty of trivial programs on radio at the time, but there were also brilliance and creativity that have never been equaled by television.” This is how Pulitzer Prize-winning oral historian Studs Terkel (1912-2008) summed up the decline in our regard for and funding of the medium in which he, as an interviewer, excelled. “The arrival of television was a horrendous thing for the medium of radio,” Terkel told Michael C. Keith, editor of Talking Radio (2000). “It was devastating for the radio artists as well as the public. Television was a very poor replacement.”

“The importance of the ‘word’ was lost when television took over the living rooms of America. Sure, there were plenty of trivial programs on radio at the time, but there were also brilliance and creativity that have never been equaled by television.” This is how Pulitzer Prize-winning oral historian Studs Terkel (1912-2008) summed up the decline in our regard for and funding of the medium in which he, as an interviewer, excelled. “The arrival of television was a horrendous thing for the medium of radio,” Terkel told Michael C. Keith, editor of Talking Radio (2000). “It was devastating for the radio artists as well as the public. Television was a very poor replacement.”

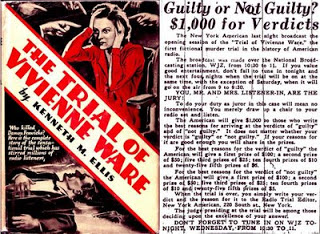

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.

“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.