Doesn’t Republican rhetoric sound tired these days? The material isn’t fit for Vaudeville. The same old folksy (make that fauxsy) references to the mythical Joe Sixpack or average Joe, plumbing and otherwise. Shouldn’t that at least be the average José by now? It all strikes me as so 1950s in its white picket-fenced-in parochialism. Tuners-in are treated to the same bromidic anecdotes that are meant to stand for what supposedly matters or to distract from what truly does.

To candidates like McCain and Palin, what matters surely isn’t the presumably average Joe or Jane, at least not as anything other than statistical figures adding up to a sufficient number of votes. What matters to Republicans is the maintaining of a status quo serving those at the top who, if they deem it fit, let a few crumbs fall from the table at which few sit and most serve. Republicans tend to appeal to our meanest instincts, greed and selfishness, for which reason they rely on the lowest common denominators in their campaign speeches and their less-than-reassuring assurances.

No new taxes? “Read my lips,” perchance? The line is familiar, even if the letdown seems to have been forgotten by most. Less government? Tell that to the average Janes whom you deny control of their own bodies and destinies. I, who might have been a US citizen by now had it not been for conservative politics, would rather have big government than a world controlled by large corporations whose profit-marginalization of humanity is not only harming national economies but, what should be more important to us than mammon, our shared, global ecology.

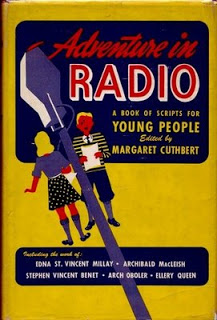

Joe the Plumber? Sure, he exists. That does not make the figure any less of a fiction, a campaign speech commodity. Listening to the final Presidential debate, I was reminded of a certain “expert plumber” who stood up against a ruthless politician clawing himself into office; a cat, no less. Back in 1940, when socialism was not quite the dirty word that it is today, playwright Arthur Miller (a revival of whose All My Sons opens on Broadway tonight) created such fierce opponents in his radio fantasy “The Pussycat and the Expert Plumber Who Was a Man” (previously discussed here).

Tom, the Pussycat in question, is a questionable campaigner who shrouds his feline identity in threats and promises; he gets elected mayor in a nasty contest relying on the exposure of past wrongs in the lives and careers of elected officials, however irrelevant such revelations might be to the act of governing.

Tom aspires to the Presidency . . . until he is confronted by a fearless plumber, a citizen who exposes him for the sly customer he really is. Beaten, Tom returns to his home. The “difference between a man and a cat,” he concludes,

is that a cat will do anything, the worst things, to fill his stomach, but a man . . . a man will actually prefer to stay poor because of an ideal. That’s why I could never be president; because some men are not like cats. Because some men, some useful men, like expert plumbers, are so proud of their usefulness that they don’t need the respect of their neighbors and so they aren’t afraid to speak the truth.

As long as there is cream there will be cats that keep their paws on it while they purr about prosperity for all. Send in some stout-hearted plumbers who refuse to be campaign fodder and, rather than having pulled the fur over their eyes, set out to realize the ideal of draining the arteries in which the cream is clotting. And don’t let cream-licking felines make you believe that an ideal such as this is nothing but the stuff of pipe dreams . . .

My grandmother refused to listen. She would walk out of the room whenever Marlene Dietrich appeared on the small screen. “She betrayed our country,” Oma would say, referring to Dietrich’s departure for Hollywood about the time the fascists came into power. Actually, Dietrich left a few years earlier; but the Nazis sure failed to lure her back. What a loss it is to turn a deaf ear to what aforementioned radio actor Joe Julian called “an exotic accent” and a “strong voice-presence.” Working with her in Dietrich’s lost radio series Café Istanbul (1952), Julian got a “glimpse behind the public image” and discovered

My grandmother refused to listen. She would walk out of the room whenever Marlene Dietrich appeared on the small screen. “She betrayed our country,” Oma would say, referring to Dietrich’s departure for Hollywood about the time the fascists came into power. Actually, Dietrich left a few years earlier; but the Nazis sure failed to lure her back. What a loss it is to turn a deaf ear to what aforementioned radio actor Joe Julian called “an exotic accent” and a “strong voice-presence.” Working with her in Dietrich’s lost radio series Café Istanbul (1952), Julian got a “glimpse behind the public image” and discovered

Sometimes, when my heart is not in in, my mind’s eye begins to stray. That was what happened a while back when I tried To Please a Lady. Tried to follow it, that is. The Lady in question is one of Barbara Stanwyck’s decidedly lesser vehicles, and the horsepower on display in it is not likely to get my heart a-racing. Still,

Sometimes, when my heart is not in in, my mind’s eye begins to stray. That was what happened a while back when I tried To Please a Lady. Tried to follow it, that is. The Lady in question is one of Barbara Stanwyck’s decidedly lesser vehicles, and the horsepower on display in it is not likely to get my heart a-racing. Still,

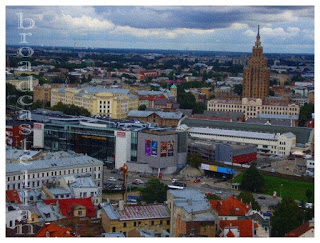

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).