Both BBC Radio 4 and 7 are in the thick of a J. B. Priestley festival, a spate of programs ranging from serial dramatizations of early novels (The Good Companions and Bright Day) and adaptations of key plays (Time and the Conways and An Inspector Calls), to readings from his travelogue English Journey and a documentary about the writer’s troubled radio days. Now, I don’t know just what might be the occasion for such a retrospective, since nothing on the calendar coincides with the dates of Priestley’s birth or death. Perhaps, it is the connection with the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of Dunkirk, an event on which Priestley embroidered in June 1941 for one of his Postscript broadcasts, that recalled him to the minds of those in charge of BBC radio programming.

Both BBC Radio 4 and 7 are in the thick of a J. B. Priestley festival, a spate of programs ranging from serial dramatizations of early novels (The Good Companions and Bright Day) and adaptations of key plays (Time and the Conways and An Inspector Calls), to readings from his travelogue English Journey and a documentary about the writer’s troubled radio days. Now, I don’t know just what might be the occasion for such a retrospective, since nothing on the calendar coincides with the dates of Priestley’s birth or death. Perhaps, it is the connection with the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of Dunkirk, an event on which Priestley embroidered in June 1941 for one of his Postscript broadcasts, that recalled him to the minds of those in charge of BBC radio programming.

Never mind the wherefores and whys. Any chance of catching up with Priestley is welcome, especially when the invitation is extended by way of the wireless, the means and medium by which his voice and words reached vast audiences during the 1930s and early 1940s, both in the United Kingdom and the United States.

For all his experience as a broadcaster, though, Priestley, who was not so highbrow as to high-hat the mass market of motion pictures, never explored radio as a playwright’s medium, as a potential everyman’s theater on whose boards to try his combined radiogenic skills of novelist, dramatist, and essayist for the purpose of constructing the kind of aural plays that are radio’s most significant contribution to twentieth-century literature—the plays of ideas.

Priestley prominently installed a wireless set in Dangerous Corner, a stage thriller whose characters gather to listen to a thriller broadcast. Later, he read his controversial wartime commentaries (titled Postscripts) to a vast radio audience. He even went on one of Rudy Vallee’s variety programs to discuss the fourth dimension. Yet the medium that relied entirely on that dimension, to the contemplation of which he devoted many of his stage plays—Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before among them—did not intrigue Priestley to make time and create plays especially for the air.

To be sure, his falling out with the BBC in 1941 (as outlined in Martin Wainwright’s radio documentary about the Postscript broadcasts) did little to foster Priestley’s appreciation of the radiodramatic arts. Yet the indifference is apparent long before his relationship with Auntie soured. When interviewed for the 1 September 1939 issue of the Radio Times about his novel Let the People Sing, which was to be read serially on the BBC before it appeared in print, Priestley dismissed the idea that he had written it with broadcasting in mind:

“I realised, of course, that the theme must appeal to the big majority. But apart from that, I thought it better to let myself go and leave the BBC to make it into twelve radio episodes. It would otherwise have cramped my style.”

To Priestley, the “experiment” of broadcasting his novel lay in the marketing “gamble” of making it publicly available prior to publication, a challenge of turning publishing conventions upside down by effectively turning the printed book into a sort of postscript. Clearly, he looked upon radio a means of distribution rather than a medium of artistic expression.

Reading I Have Been Here Before and listening to the radio adaptation of Time and the Conways, I realized now little either is suited to the time art of aural play. Whereas the Hörspiel or audio play invites the utter disregard for the dramatic unities of time and space, Priestley relied on the latter to make time visible or apparent for us on the stage.

The Conways, like the characters of Dangerous Corner before them, are brought before us in two temporal versions, a contrast designed to explore how destinies depend on single moments in time—moments in which an utterance or an action brings about change—and how such moments might be recaptured or rewritten to prevent time from being, in Hamlet’s words, “out of joint.”

“Time’s only a dream,” Alan Conway insists. “Time doesn’t destroy anything. It merely moves us on—in this life—from one peep-hole to the next.” Our past selves are “real and existing. We’re seeing another bit of the view—a bad bit, if you like—but the whole landscape’s still there.”

In Priestley’s plays, it is the scenery, the landscape of stagecraft, that remains there, “whole” and virtually unchanged. The unity of space is adhered to so as to show up changes in attitudes and relationships and to maintain cohesion in the absence or disruption of continuity.

In radio’s lyrical time plays, by comparison, neither time nor place need be of any moment. It is the moment alone that matters on the air, an urgency that Priestley, the essayist and wartime commentator, must surely have sensed. Priestley, the novelist and playwright did or could not. Too few ever did. To this day, a whole aural landscape is biding its time . . .

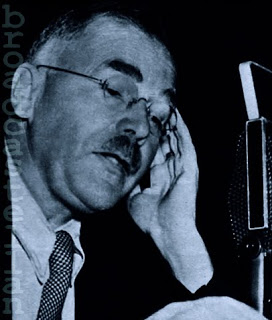

“Education comes more easily through the ear than through the eye,” H. V. Kaltenborn declared back in 1926. He had to believe that, or needed to convince others of it, at least. After all, the newspaper editor had embarked on a new career that was entirely dependent on the public’s ability to listen and learn when he, as early as 1921, first stepped behind a microphone to throw his disembodied voice onto the airwaves, eventually to become America’s foremost radio commentator. Writing about “Radio’s Responsibility as a Molder of Public Opinion,” Kaltenborn argued education to be the medium’s “greatest opportunity.” And even though the opportunity seized most eagerly was advertising, some sixty American colleges and universities were broadcasting educational programs during those early, pre-network days of the “Fifth Estate.”

“Education comes more easily through the ear than through the eye,” H. V. Kaltenborn declared back in 1926. He had to believe that, or needed to convince others of it, at least. After all, the newspaper editor had embarked on a new career that was entirely dependent on the public’s ability to listen and learn when he, as early as 1921, first stepped behind a microphone to throw his disembodied voice onto the airwaves, eventually to become America’s foremost radio commentator. Writing about “Radio’s Responsibility as a Molder of Public Opinion,” Kaltenborn argued education to be the medium’s “greatest opportunity.” And even though the opportunity seized most eagerly was advertising, some sixty American colleges and universities were broadcasting educational programs during those early, pre-network days of the “Fifth Estate.”