Language is to me one of the main pulls of the no longer popular, be it American radio comedy of the 1940s or the serial novels of the Victorian era. That is to say, the absence of the kind of language we refer to as “language” whenever we caution or implore others to mind theirs. Mind you, all manner of “language” escapes me in moments of physical or mental anguish; but, once I hit the keyboard, whatever hit me or made me hit the roof is being subjected to a process of Wordsworthian revision. You know, “emotion recollected in tranquility.”

If the revisions come off, what remains of the anger or hurt that prompted me to write has yet the kind of medium rare severity that renders expressed thought neither raw nor bloodless. No matter how many words have been crossed out, the recollection still gets across whatever made me cross in the first place, and that without my being double-crossed by lexical recklessness.

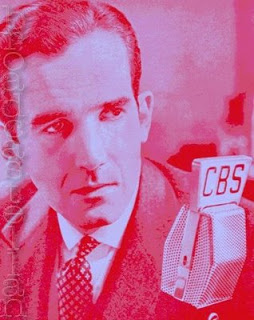

Writing with restraint is not a matter of adopting certain mannerisms to avoid being plain ill-mannered. Obscurity is hardly preferable to obscenity. The trick is to create worthwhile friction without resorting to diction unworthy of the cause—without using the kind of words that just rub others the wrong way. I was certainly rubbed so when, researching old-time radio, I brushed up on Amiri Baraka’s Jello (1970), no doubt the angriest piece of prose ever to be written about the American comedian Jack Benny (seen here, dressing up as Charley’s Aunt).

Jello was penned at a time when many Americans who grew up listening to Benny retreated into nostalgia rather than face, accept, let alone support the radical cultural changes proposed or, some felt, threatened by the civil rights movement. Baraka confronted this longing for the so-called good old days with a farce in which Benny’s much put upon valet Rochester refuses the services the public had long—and largely unquestioningly—come to expect of the well-loved character.

What ensues is a riot—albeit not one of laughs—as Baraka’s “postuncletom” Rochester lashes out at his former master-employer and insists on forcefully taking the money out of which he believes to have been cheated during the past thirty-five years (according to Baraka’s rewriting of broadcasting history). Having found that “loot” in a bag of Jello, Rochester leaves Benny, Mary Livingstone, and Benny regular Dennis Day to their “horrible lives!”—piled up on the floor like the corpses in a Jacobean revenge tragedy.

The plot of Jello is older than its message—the call to rise against the forces that made, made tame or threaten to unmake us; and the only startling aspect of Baraka’s play is the aggressive tone in which that message is delivered, delivered, to be sure, to none but those already alive and receptive to his rallying call.

“No, Mary,” Baraka’s version of Benny insists, “this is not the script. This is reality. Rochester is some kind of crazy nigger now. He’s changed. He wants everything.” The language alone signals that we are well beyond the grasp of the titular sponsor, beyond the code adopted in the summer of 1939 by the National Association of Broadcasters, according to which “no language of doubtful propriety” was to pass the lips of anyone on the air.

As is the case in all attempts at policing language, the underlying thought—the unsaid yet upheld—might be more dubious still; and when Baraka picks up the word “nigger,” he gives expression to a hostility that could not be voiced but was played out in and reinforced by many of the networks’ offerings. Indefensible, however, is his use of equally virulent language like “stupid little queen” and “highvoiced fag” when referring to tenor Dennis Day or “radio-dikey,” as applied to Mary Livingstone. Staging revolution, Baraka is upstaged by revulsion. He has mistaken the virulent for the virile.

In those days and to such a mind, “fag” was just about the most savage term in which to couch one’s rejection of the unproductive and the non-reproductive alike. It was a monstrous word demonstrative of the fear of emasculation. It is that fear—and that word—with which power and dignity was being stripped from those whose struggle for equality was just beginning during the days following the Stonewall Riots of 28 June 1969, from those whose fight was impeded by a fear greater and deeper even than racism.

Now, I’m no slandered tenor; but I have been affronted long enough by such verbiage to be tossing vitriol into the blogosphere, to be venting my anger or frustration in linguistically puerile acts of retaliation. If I pick up those words from the dust under which they are not quite buried, I do so to fling them back at anyone using them, whether mindlessly or with design—but especially at those who inflict suffering in the fight to end their own. Our protests and protestations would be more persuasive by far if only we paid heed to the words we should strike first.

Related writings

“A Case for Ellery Who?: Detecting Prejudice and Paranoia in the Blogosphere”

“Martin Luther Kingfish?: Langston Hughes, Booker T. Washington, and the Problem of Representation”

“Jack Benny, Urging Americans to Keep Their Wartime Jobs, Catches Rochester Moonlighting in Allen’s Alley”

I rarely hear from my sister; sometimes, months go by without a word between us. I have not seen her in almost a decade. Like all of my relatives, my sister lives in Germany. I was born there. I am a German citizen; yet I have not been “home” for nearly twenty years. It was back in 1989, a momentous year for what I cannot bring myself to call “my country,” that I decided, without any intention of making a political statement about the promises of a united Deutschland, I would leave and not return in anything other than a coffin. I don’t care where my ashes are scattered; it might as well be on German soil—a posthumous mingling of little matter. This afternoon, my sister sent me one of her infrequent e-missives. I was sitting in the living room and had just been catching up with the conclusion of an old thriller I had fallen asleep over the night before. The message concerned US President Obama’s visit to Buchenwald, the news of which had escaped me.

I rarely hear from my sister; sometimes, months go by without a word between us. I have not seen her in almost a decade. Like all of my relatives, my sister lives in Germany. I was born there. I am a German citizen; yet I have not been “home” for nearly twenty years. It was back in 1989, a momentous year for what I cannot bring myself to call “my country,” that I decided, without any intention of making a political statement about the promises of a united Deutschland, I would leave and not return in anything other than a coffin. I don’t care where my ashes are scattered; it might as well be on German soil—a posthumous mingling of little matter. This afternoon, my sister sent me one of her infrequent e-missives. I was sitting in the living room and had just been catching up with the conclusion of an old thriller I had fallen asleep over the night before. The message concerned US President Obama’s visit to Buchenwald, the news of which had escaped me.