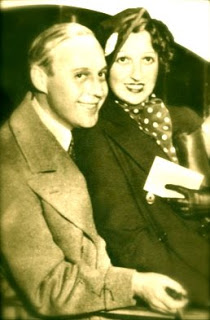

As I add another candle to the cupcake set aside for the celebration of my fourth blogging anniversary and to be consumed in the solitude of my virtual niche, I am once again wondering whether I should not have taken a scandal sheet out of Louella Parsons’s cookbook. You know, serving it while it’s hot, with a pinch of salt on the side. Dishing it out in a bowl the size of China, a tidbit-craving multitude hanging on your gossip-dripping lips. As the first name in name-dropping, Louella (seen below, cutting her own birthday cake, anno 1941) might have done well as a webjournalist, just as she had on the air, despite a lazy delivery that piled fluffs on fluff and a flat voice that makes Agnes Moorehead sound like a Lorelei by comparison. Her hearsay went over well all the same, its nutritional deficiencies giving none cause for contrition.

As I add another candle to the cupcake set aside for the celebration of my fourth blogging anniversary and to be consumed in the solitude of my virtual niche, I am once again wondering whether I should not have taken a scandal sheet out of Louella Parsons’s cookbook. You know, serving it while it’s hot, with a pinch of salt on the side. Dishing it out in a bowl the size of China, a tidbit-craving multitude hanging on your gossip-dripping lips. As the first name in name-dropping, Louella (seen below, cutting her own birthday cake, anno 1941) might have done well as a webjournalist, just as she had on the air, despite a lazy delivery that piled fluffs on fluff and a flat voice that makes Agnes Moorehead sound like a Lorelei by comparison. Her hearsay went over well all the same, its nutritional deficiencies giving none cause for contrition.

On this day, 20 May, in 1945, for instance, Louella rattled off this farraginous list of “exclusives”: that silent screen star Clara Bow was “desperately ill again” after suffering a “complete nervous breakdown”; that Abbott and Costello would “not even speak to each other” on the set of their latest movie; that the Cary Grant-Betty Hensel romance was “beginning to totter”; and that “forty Hollywood films ha[d] been dubbed in German” to “counteract the dirty work done by Goebbels.” Just as you finally prick up your ears, indiscriminate Lolly snatches the plate from under your nose.

As an item of “last-minute news,” Louella announced that, with John Garfield going into the navy, his part opposite Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice was to be played by Van Heflin, who had just received his medical discharge. Doesn’t ring true, does it? Well, that’s the problem with promising “the latest.” It rarely is the last word.

Not that being belated renders your copy free from gaffes and inaccuracies, to which my own writing attests. Yet it isn’t the need to be conclusive or the vain hope for the definite that makes me resist what is current and in flux. I’m just not one to reach for green bananas and speculate what they might taste like tomorrow. I won’t bite when the gossip is fresh; my teeth are in the riper fruit.

So, there is little in it for me to drop names, and pronto. Rather than playing Louella, I fancy myself another Darwin. Darwin L. Teilhet, that is, a fiction writer and early reviewer of American radio programs; he was born 20 May 1904, 101 years to the day that my journal got underway.

It is easy for me to identify with Teilhet, who loved the so-called blind medium without turning a blind eye to the shortcomings of its offerings. In his column in the Forum for May 1932, for instance, he complained that the “dramatic machinery” of Amos ‘n’ Andy “creaks,” but nonetheless insisted that the declared that the “art of broadcasting” was “entirely too important to be ignored or squelched by derogatory attacks. The time, he argued, was

ripe for the conception of a new genus of critic with the radio as his field.

Intelligently and conscientiously pursued over a period of time, it [the criticism of radio programs] might not only draw to itself a large number of followers among the radio audience but actually have some effect in improving the quality of the programs which are directed at them.

Today, a reviewer of such programs cannot expect to garner any sizeable number of followers, much less to have an effect on what aired decades ago. Tuning in, like virtue, is its own reward; and though the time may not be ripe for the likes of me, it sure seems ripe for the rediscovery of the presumably out-of-date. In these days of economic recession, we might find a return to the low-budget dramatics of radio particularly worthwhile. I, for one, would make the pitch to the networks that abandoned the genre half a century ago.

Time to blow out the candles and get on with it.

Related writings

First entry into this journal

First anniversary

Second anniversary

Third anniversary

Last night, I felt like an old queen. Granted, that is not an uncommon feeling for me; but the Queen in this case was none other than Victoria, who, in the last years of her reign, enjoyed partaking of live opera without actually having to leave for the theater at which it was presented. Her royal box was a contraption called the Electrophone, a special telephone service that connected subscribers with the theaters from which the sounds of music and drama could be appreciated while being seated in whichever armchair one designated as a listening post. Today, we may be accustomed to live—or, wardrobe malfunctions notwithstanding, very nearly live—broadcasts of sounds as well as images; but last night’s event felt as new and exciting to me as it must have been picking up the electrophone or dialing in to those experimental theater relays during the 1890s and 1920s, respectively.

Last night, I felt like an old queen. Granted, that is not an uncommon feeling for me; but the Queen in this case was none other than Victoria, who, in the last years of her reign, enjoyed partaking of live opera without actually having to leave for the theater at which it was presented. Her royal box was a contraption called the Electrophone, a special telephone service that connected subscribers with the theaters from which the sounds of music and drama could be appreciated while being seated in whichever armchair one designated as a listening post. Today, we may be accustomed to live—or, wardrobe malfunctions notwithstanding, very nearly live—broadcasts of sounds as well as images; but last night’s event felt as new and exciting to me as it must have been picking up the electrophone or dialing in to those experimental theater relays during the 1890s and 1920s, respectively.