The presumably out-of-date with which I choose to concern myself in this journal cannot be expected to have an air of minty freshness about it; but by now broadcastellan is beginning to smell downright musty. Still, I cannot quite muster the energy to attend to the cobwebs in which this nugatory niche is shrouded. The state of neglect is owing to the dust that has enveloped my carcass of late. For the past three weeks or so, we have been engrossed in the project of renovating a late-Victorian house we intend on calling home in a few short weeks from now, or whenever the central heating and at least one of the bathrooms are installed.

Each day, it is becoming a little easier for me to see past the rubble and imagine myself lolling there, keeping up with past in the leisurely and blissfully inconsequential manner to which I have become so readily accustomed. Until that can happen, though, I shall have to go back, again and again, to scrape floors, strip wallpaper, and remove whatever trace we find of those who lived in there immediately before us, all the while uncovering the more distant past they deemed it fit to hide behind layers of outmoded modernity.

Aside from the dirt and the all too apparent signs of aging, the only thing I seem to have in common with this place is the state of being pre-occupied. It isn’t the work alone and the costs involved that weigh on my mind. It is my own history of habitation on which I feel compelled to dwell. I am reminded of the time when my father decided to get us out of that working class neighborhood whose drabness and influx of foreign workers must have seemed a stigma to him but that was to prepubescent me the only world I knew . . . and one shared by a great many kids my age.

Sure, the prospect of having, for the first time in my life, a room of my own was exciting; but the move, some fifteen miles from where I had grown up, came at a great price . . . including the loss of my ability to communicate, to make myself understood and others laugh (something that was important to me, being that I felt too short to be good at much else). Regional dialects were very pronounced back then in Germany; and moving even that short distance meant that I could barely follow what folks were saying, let alone lead them in laughter. I remember our neighbor asking my sister and me whether we had come to help our father build the house. “Yes,” I said, expectantly. I thought the man had just offered me a couple of peaches. That’s how it sounded to me, anyhow. Life wasn’t going to be a bowl of fruit.

For my parents, it was the picket fence dream coming true (without the picket fence, mind you, which is an American cliché). Still, being working class, no matter how hard we tried to come across otherwise, meant that the house was coming along only gradually—which is why my mother could relate to Petrocelli.

Petrocelli was a mid-1970s crime drama, and a pretty formulaic one at that. The action unfolded in flashbacks, from crime to prosecution; but it always ended in the present—and that present was a construction site. After each case, defense lawyer Petrocelli went to inspect the progress on his new home, the one his job helped to build. Week after week, there was little noticeable change, a state of incompletion that made it easy for my mother to identify with the frustrated ambitions of the titular character.

As for myself, I felt it difficult to relate to anything or anyone back then. Everything was unfamiliar and new (even the ledgers I had filled with pictures and stories had been discarded during the move), and apart from the promise of having that room to myself, nothing seemed worth the trouble of giving up so much of what had felt like home to me, no matter how it might have looked to a status-conscious adult.

To this day, putting tens and hundreds of thousands into a single project like building or doing up a house is troubling to me. Rather than the financial risk and the potential hardship it poses, it is the peril it can mean to one’s sense of home. You see, the house my father built was never to become our home. It meant the end of our family—the end of all family activities for which there was no money left in the budget, the end of my parents’ marriage and, ultimately albeit indirectly, my father’s life.

In retrospect, that new house—the dream of being a four-walled somebody—looks an awful lot like a Petrocelli flashback . . . a wrong move and a slow process of undoing.

Today, 25 July 2008, would have been the 85th birthday of Estelle Getty, who passed away last Tuesday. Since I was unable to share my thoughts here on that night, I shall do so now. The actress was on my mind that very night, before I even learned about her death. There is nothing uncanny about that, though. I often think, talk about—even talk like—Ms. Getty and the Girls.

Today, 25 July 2008, would have been the 85th birthday of Estelle Getty, who passed away last Tuesday. Since I was unable to share my thoughts here on that night, I shall do so now. The actress was on my mind that very night, before I even learned about her death. There is nothing uncanny about that, though. I often think, talk about—even talk like—Ms. Getty and the Girls.  Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”

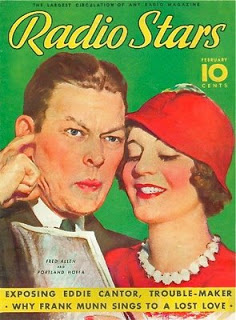

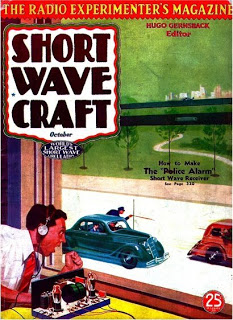

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”