“It’s not the end of the world.” How often do we utter those words, whether to calm ourselves or to dismiss the concerns of others. Well, I never found anything calming about that expression. It is the belittling by hyperbole that irks me. We tend to judge the gravity of a situation by the magnitude of its physical manifestations rather than the depth of feelings it produces in the experiencer. I, for one, have experienced the end of the world in early childhood; yet there is no evidence of an event having taken place, no trace of its existence save for the lachrymal salt on a crumpled pillow that, I suppose, was disposed of decades ago. No surface trace, that is.

One evening, in a working-class flat in the grim sterility of the German industrial town I was expected to call home, I overheard my parents make mention of the apocalypse. Someone had predicted that the world was going to end, and the date was set for the night to come. It was one of those doomsday prophecies that adults shrug off or subscribe to, depending on their intellect, faith and psychological make-up. As a child, I had no recourse to experience. I had no knowledge of having survived any number of doomsdays pronounced previously. Nor did I yet doubt that adults knew all and spoke true. I only had that night to go into, with a sense that it would be my last.

I was put to bed, and it felt as if I had been abandoned, cast out to face the unfathomable by myself. I was going to be no more. Everything I knew was to turn into unknowable nothingness. No one seemed troubled to prepare me for this chaos, the void that I already felt lying alone in the dark. I remember well the agony of that night, an angst that I now might term existential.

I have no recollection of the morning after. What followed, though, were years of nightmares involving the atom bomb, cold-war sweat inducing anxieties about nuclear fallout and the nihilism of the No Future generation, mingled, in my case, with an awareness of my queer otherness that made it seem impossible for me to go into those nights in a fellowship of the doomed.

No doubt, this is why Ernest Hemingway’s short story “A Day’s Wait” appealed to me when I first read it as a teenager. It is a story of a boy who, owing to a momentous misunderstanding, believes himself to be dying. It is that story I chose to write about as an undergraduate student in English literature, even though it has often been dismissed as a minor work of magazine fiction beyond the canon of Hemingway’s supposed greatest. I, on the other hand, was drawn to what I read as its theme of trivialized sublimity and the terror of that trivialisation.

Until recently, I did not consider that my first last night might have been the beginning of the end, not of childhood – a concept I have long come to question – but of trust, faith, love and a sense of order and stability. Now, as I am preparing for a lecture on gothic ruins, I am piecing together those haunting, Frankensteinean fragments of my past and present selves, and I wonder just how much fell apart that one nightfall …

[This entry is dedicated to the students of my Gothic Imagination class, whom, during the last few weeks, I exposed to visualisations of nightmares, sublime views and dystopian visions.]

“. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture.

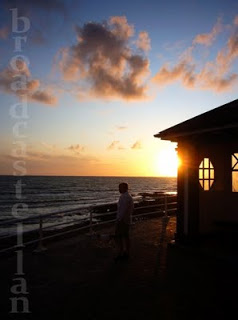

“. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture. Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.”

Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.” On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . .

On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . .