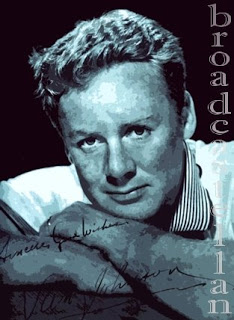

I am not sure who came up with the moniker “the voiceless Sinatra,” which is attached to virtually every obituary of and tribute for Van Johnson, the Hollywood actor who died on 12 December 2008 at the age of 92. Apparently, the coining of the phrase dates back to the mid-1940s and was meant to capture the boy-next-door’s appeal to teen-aged moviegoers (audible in the 11 December 1945 Theater of Romance introduction to Love Affair). It is a misleading label nonetheless, considering that Johnson was heard in musicals and had many a voice-only part in the so-called theater of the mind. Back in 1985, I saw him on the New York stage, when he starred in La Cage Aux Folles, the first Broadway musical I ever saw. Johnson’s show business career was long and diverse, if slow in becoming distinguished.

I am not sure who came up with the moniker “the voiceless Sinatra,” which is attached to virtually every obituary of and tribute for Van Johnson, the Hollywood actor who died on 12 December 2008 at the age of 92. Apparently, the coining of the phrase dates back to the mid-1940s and was meant to capture the boy-next-door’s appeal to teen-aged moviegoers (audible in the 11 December 1945 Theater of Romance introduction to Love Affair). It is a misleading label nonetheless, considering that Johnson was heard in musicals and had many a voice-only part in the so-called theater of the mind. Back in 1985, I saw him on the New York stage, when he starred in La Cage Aux Folles, the first Broadway musical I ever saw. Johnson’s show business career was long and diverse, if slow in becoming distinguished.

Many of his early roles were little more than featured bit parts designed to draw attention to the young hopeful on the MGM lot. As was the case with many a rising star, radio assisted in his promotion. Along with first-billed Edward Arnold and his co-star Fay Bainter, Johnson was given the opportunity to reprise his role in The War Against Mrs. Hadley for the in a Lux Radio Theater, in a broadcast commemorating the first anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor (7 December 1942). Introducing the players, host Cecil B. DeMille referred to Johnson as one of Hollywood’s “promising newcomers.”

Due to a severe accident, Johnson very nearly did not get a chance to make good on that promise. Barred from military action, he served his country on the home front, appearing in a string of wartime pictures, including The Human Comedy, A Guy Named Joe, and Thirty Seconds over Tokyo. Last night, I saw him in The White Cliffs of Dover. In it, Johnson plays the hapless admirer of a young woman (Irene Dunne) who visits England shortly before the Great War, falls in love and stays. Johnson is seen in the opening scene, but has only one memorable moment thereafter when he gets to kiss his married sweetheart during a chance encounter. I suppose MGM had so many stars back then that it could afford such frivolous casting.

Throughout the Second World War, Johnson remained “one of the screen’s most rapidly rising young personalities,” as he was billed on the 2 November 1944 broadcast of Suspense. Since his fine performance in “The Singing Walls” is not available on the Internet Archive, where you will hear Preston Foster and Dane Clark instead (in a 2 September 1943 production of the play), I have temporarily made the recording available here..

Johnson returned to Suspense four times, namely for ”The Defense Rests” (6 October 1949), ”Salvage” (6 April 1950), ”Strange for a Killer” (15 March 1951), and “Around the World” (6 April 1953).

Aside from his numerous dramatic performances on the air, including the Theatre Guild’s non-musical presentation of State Fair (4 January 1953), Van Johnson was also heard singing “Pennies from Heaven” as a tribute to an ailing Bing Crosby on The Big Show (1 April 1951). “I haven’t been singing much since I’ve been in pictures,” the former “song-and-dance man” warned his hostess after performing in a scene from his upcoming picture Go for Broke (1951), “My voice might crack.” Well, whatever Bob Hope’s cracks, “Go for Croak” he did not. Van Johnson’s was not such bad record for someone allegedly “voiceless.”

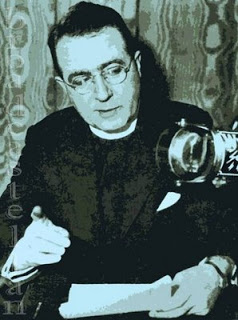

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey,

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey,

“Ladies and gentlemen. We take you now to New York City for the annual tree lighting ceremony: Click.” Imagine the thrill of being presented with such a spectacle . . . on the radio. You might as well go fondle a rainbow or listen to a bar of chocolate. Even if it could be done, you know that you have not come to your senses in a way that gets you the sensation to be had. I pretty much had the same response when I read that BBC Radio 4 was going to air a documentary on the Three Stooges.

“Ladies and gentlemen. We take you now to New York City for the annual tree lighting ceremony: Click.” Imagine the thrill of being presented with such a spectacle . . . on the radio. You might as well go fondle a rainbow or listen to a bar of chocolate. Even if it could be done, you know that you have not come to your senses in a way that gets you the sensation to be had. I pretty much had the same response when I read that BBC Radio 4 was going to air a documentary on the Three Stooges.