Writing this journal, I often think of myself as being on the verge of extinction. A sense of pastness pervades my present, delayed responses to the supposedly bygone, with modern technology determining (and potentially terminating) my virtual presence. In my largely inconsequential musings on popular culture, I am perched on the edge of both nostalgia and history, dreading the irresponsibility and the impossible responsibilities of such territories foreign to me. At best, I can represent myself—and that but feebly, squeezed in as I am by the marginalia, the marginality of my interests, intellect, and imagination.

Writing this journal, I often think of myself as being on the verge of extinction. A sense of pastness pervades my present, delayed responses to the supposedly bygone, with modern technology determining (and potentially terminating) my virtual presence. In my largely inconsequential musings on popular culture, I am perched on the edge of both nostalgia and history, dreading the irresponsibility and the impossible responsibilities of such territories foreign to me. At best, I can represent myself—and that but feebly, squeezed in as I am by the marginalia, the marginality of my interests, intellect, and imagination.

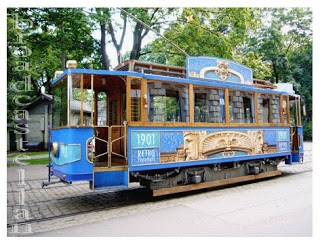

A quest of self between the nowhere of nostalgia and the distinct there—and therefores—of history? Somehow, that is not unlike riding the retro tram that takes visitors to Latvia through the nation’s capital, Riga. No wonder. I recently returned from there.

The “Retro Tram” takes you to the Jugendstil district, where you will find the largest accumulation of art nouveau architecture in the world (a designated World Heritage site); it also takes you to Riga’s garden city, Mezapark and its nouveau riche . . . past the Latvian National Opera, the Riga Latvian Society, the National Library of Latvia, past and through a series of cemeteries, all the way to the Riga National Zoological Garden. National! That elusive, loathsome, longing-inspiring notion.

Even though it numbers among the world’s less-than-happy countries, if a recent survey is to be believed, Latvia strikes one—or struck me—as a young nation eager to find and define itself. Wars, occupations, repressions of native culture and language, and now the surge (or scourge) of Western commercialism have made this a difficult and perhaps impossible project. One such commercial enterprise, the Retro Tram, takes you—the tourist—past sites revealing German influences and bygone splendor, while much of the old town seems like a theme park—or the construction site for one—featuring new buildings meant to reflect one past while obscuring a more recent, the horrors of which are reenacted or displayed in some of the city’s museums (the Occupation Museum, for instance). Are these places representative of the nation or placeholders for a national identity lost in (or to) the spirit of European unity?

Even though it numbers among the world’s less-than-happy countries, if a recent survey is to be believed, Latvia strikes one—or struck me—as a young nation eager to find and define itself. Wars, occupations, repressions of native culture and language, and now the surge (or scourge) of Western commercialism have made this a difficult and perhaps impossible project. One such commercial enterprise, the Retro Tram, takes you—the tourist—past sites revealing German influences and bygone splendor, while much of the old town seems like a theme park—or the construction site for one—featuring new buildings meant to reflect one past while obscuring a more recent, the horrors of which are reenacted or displayed in some of the city’s museums (the Occupation Museum, for instance). Are these places representative of the nation or placeholders for a national identity lost in (or to) the spirit of European unity?

It seemed appropriate that the tram is departing from and returning to a street whose name bespeaks or proclaims the quest for such solidarity, for union and the voicing of uniting ideas in a language that unites: Radio, McLuhan’s “tribal drum.” As I am returning now to Radio Street, to the subject that is right up mine, I struggle once more to make the past my present while steering clear of both the headlongevity of nostalgia and the impossible burden—the hubris—of history. All I can offer is a splash in the shallow puddles of my own reflections as I make my way down what, to me, is anything but Memory Lane . . .

She played tougher than anyone else in pictures, and she was better at it. She could get a guy to fall for her and a fall guy to do anything for her, be it to lie, cheat, or kill. To please her was a dangerous game; but to displease her was a deadly one. She could make puppets of men;

She played tougher than anyone else in pictures, and she was better at it. She could get a guy to fall for her and a fall guy to do anything for her, be it to lie, cheat, or kill. To please her was a dangerous game; but to displease her was a deadly one. She could make puppets of men;