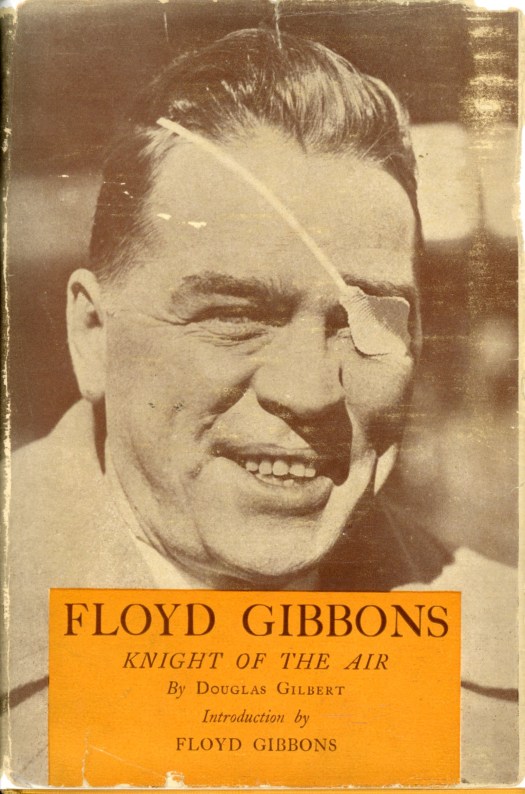

“Have voice, will travel.” That was the line my history of broadcasting professor Frank Kahn used to advertise his vocal services in the trade papers of yesteryear. And a voice for radio he did have, even though what he said and how he brought it across was appreciated by next to no one at Lehman College in the Bronx, where he ended up teaching in the cable TV age. Kahn was out of touch and, no doubt, keenly aware of it, incapable or unwilling though he was to do anything about it. “Have voice, will travel”? I mean, who among his students even got this sly reference to a time when the medium of radio was being challenged by sharp-shooting television? “Have voice, will travel.” The line came to mind when, some time ago, I read Douglas Gilbert’s biography Floyd Gibbons: Knight of the Air (1930).

You don’t have to be out of touch to appreciate it, though it sure doesn’t hurt any if you catch up with someone whose fifteen minutes of fame (and airtime) was up nearly three-quarters of a century ago.

“There is no one in the world who can talk like Floyd Gibbons,” his biographer marvelled:

He speaks at a maximum speed of 245 words a minute and at an average speed of 216 words a minute and every word is clearly pronounced, completely enunciated, readily understood. He dramatizes his speech, just as he dramatizes the news.

Gilbert, in turn, “dramatizes” Gibbons’s career. Indeed, he melo-dramatizes it. The biographer seems determined to turn the journalist into a swashbuckler and to imbue with romance what, on the air, was down-to-earth and up-to-date.

“He could, and often does, wear any sort of costume,” Gilbert says about Gibbons, “and when he does, he has an air. It is a negligent and yet perfect air.” Shown with his signature patch (Gibbons lost one eye while, as a newspaper journalist, he was reporting from French battlefields during the First World War), the so-called “Headline Hunter,” then middle-aged, certainly has that “air” of romance about him.

According to Gilbert, Gibbons was through being a roving reporter at the age of forty. His latest book, The Red Napoleon, which he was in the process of completing back in 1928, was a “prophesy of the next world war and the part radio was to play in it.” To make such a prophesy, Gibbons consulted NBC president M. H. Aylesworth; and out of his luncheon with the radio executive there “developed the ‘Headline Hunter’ and the ‘Prohibition Poller’ and news gatherer that ma[de] the Literary Digest’s fifteen minutes over WJZ a radio ‘front page.’”

At 40 through with roving? Today at 42 he’s just begun—roaming for fifteen-million persons—their vicarious vagabond of the air, satisfying the gypsy lust of those of us who have never traveled.

“He’s radio’s knight errant,” Gilbert insists, “the listener’s passport to uncharted harbors; their open sesame to Cathay; their vista of a world whose only boundaries are the poles.”

For his audition, performed in front of an “unseen audience of Aylesworth and other NBC officials,” Gibbons recounted his “most exciting experience”—being aboard the Laconia when she was torpedoed. The event had taken place over a decade earlier, on 25 February 1917; but Gibbons managed to bring it to life and to lend it urgency through the power of his voice.

Back in 1917,

Gibbons had had a hunch, a newspaper man’s hunch when he took the Laconia. He had been ordered to France as war correspondent. He refused to go on the ship on which Von Bernsdorff [German ambassador to the US] was sailing because he knew no harm would come to that ship from the Germans. He chose the Laconia, having a hunch she would be sunk and that he would escape and file a story of the sinking.

In the late 1920s, there was no indication that radio, too, was a ship under fire. As Gilbert suggests, Gibbons would have gotten aboard anyway, had he known just how much danger lay ahead. Not many people beside Gibbons imagined in 1930 that radio would become the medium most called upon for up-to-date accounts of warfare. Had he been born a decade or two later—and not died in 1939—Gibbons would have gone straight into the thick of it and brought his spitfire delivery to a medium to which his voice was so adequately equipped. Living too early, living too late? All we can hope is that our voices will travel some distance once we are convinced we have something to say . . .