What a fitting end this was to a mostly “stinky” 2021. Just as I was plonking myself down to subject my unsuspecting husband to a viewing of Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), news reached me of Betty White’s death. The year could hardly have expired on a more cheerless note, with the last of the Golden Girls not living to see her hundredth birthday in January 2022. Like so many other celebrations these days, that centenary now has to be called off as well. As the clock ticked relentlessly toward midnight, I shed a tear, remembered the laughter and called to mind the many years I spent in the company of … Rose Nylund.

I know that White, who started out on radio, played many roles on screens small and big. I also know better than to confuse an actor interpreting a script with a person inhabiting a character. Nevertheless, it was as Rose on The Golden Girls that White had the most profound influence on my life, especially in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I was trying to adopt a more colloquial American English, to make the vernacular mine and make it work for me to boot.

Now, I’m not one to “blow my own gertögenflögen” – or however you might spell Rose’s pseudo-Scandinavian additions to my vocabulary – but, with the aid of White’s Rose, I managed to find the joy in speaking in at least two tongues, resigned to the likelihood that none quite conveys what I am aiming to say, particularly in the face of that “precise moment when dog do turns white.”

Peroxide blonde like me, White’s Rose was reassuringly naïve, curious and enthusiastic. She was generally good-natured and, trusting in fellow human beings she remained even after the end of her relationship with the man she had assumed to be Miles, was especially kind to animals, among them Mr. Peepers, the cat she reluctantly gave up on the day she met her future housemate Blanche Devereaux; Count Bessie, the piano-playing chicken she dreaded consuming; and Baby, the aged pig she agreed to adopt – or indeed to all the injured animals back on the farm on which she grew up. Rose’s character and the situations in which she found herself reflected White’s commitment to animal activism.

Rose was an outsider, too, an adopted child (with a monk for a father, no less). After the death of her husband, Charlie – of whom the bull on her family farm “would have been jealous” – she moved from Minnesota to Florida, struggling to acclimatize. She felt even more out of place visiting the “Big Potato.” Never having “seen so much of everything” in her “whole life,” she did not know “how people live here.”

Rose was also highly competitive, filled as she was with the “bitter butter memories” of having lost Butter Queen – a disappointment she revisited on the night she was arrested for prostitution – and occasionally exhibited a sarcastic streak, all qualities that I possessed anno 1990 without quite having the language to give them adequate expression in my temporary home of NYC.

Rose, as brought to life by White, never left me; indeed, the Girls helped me when I relocated from Manhattan to Wales, ill equipped as I was in my knowledge of that nation. Only yesterday, in the shower, I was making up another St. Olaf story that Rose might have tried to spring on Blanche, Dorothy and Sophia – a story sure to sound incomprehensible beyond that shower door.

I am used to talking to myself, unable to make myself understood about my distant past, which is another country not on anyone else’s map. Like Rose, though, I never quite stopped trying.

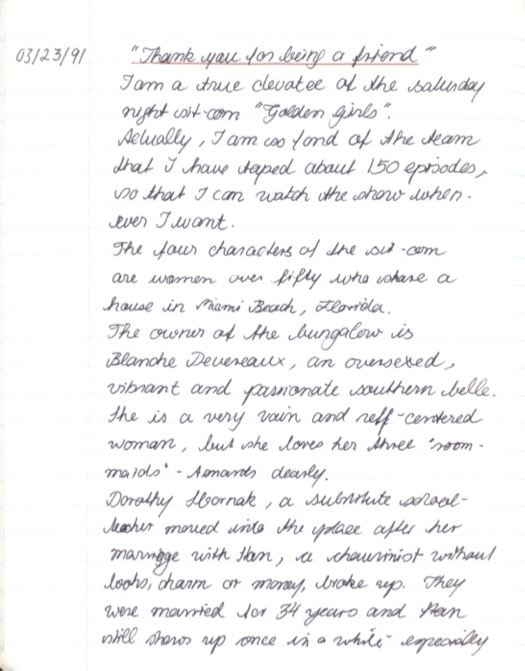

On 23 March in 1991, during my first semester of college at BMCC in downtown Manhattan, and toward the end of what would be the final season of The Golden Girls, I devoted an entry to the girls in my journal – an assignment for my English 101 class with Ms. Padol – insisting that those “four women [we]re not just knitting sweaters.” After all, there were “episodes on artificial insemination, gay marriage, racial problems, Alzheimers, homeless[ness] and death.” As I pointed out to my audience of one, “the show is liberal but does not come along too preaching or moralising.”

When you keep watching the show you come to know the characters[,] learn a lot about their relationship. And even though the four leading ladies are slightly off-beat you can get a lot out of the show; you can often relate to some of their various problems.

There is life and sex after 50. Some youngsters seem to forget that and some old people find it hard to compete or fight for their rights in the fast-paced world of today

As a queer young man growing up at the height of the AIDS crisis in the West, I certainly could relate to Rose and her agony of waiting for the result of an HIV test. I found comfort in the fiction that they had made it past the age of forty and envied the close and safe commune of the Girls. When I taught an English literature class on friendship back in the late 1990s, I played the theme song that had inspired the theme of my class.

Now that I am over fifty (Rose was 55 in the first season of the show, even though White was already in her sixties then), I think of The Golden Girls as a cultural product that made it easier for me to transition from silver to gold. And while I did not pick up many medals along the way, I did it all without access to the professional services of Mr. Ingrid of St. Olaf and his moose. Rose never divulged which part of the moose he used. “But,” she declared, “it’ll keep your hair in place in winds up to 130 miles an hour.”

I could always count on Betty White to see me through a storm.

What the Bwana Devil! I’ve been trying on various kinds of glasses to take in Channel 4’s 3D fest—but none transport me into the third dimension. Turns out, viewing the weeklong series of films and specials, culminating in a “3-D Magic Spectacular” and a clipfest of “The Greatest Ever 3-D Moments”—requires special goggles that can only be obtained from a certain chain of supermarkets whose reach does not extend to Mid Wales. By the time we got around to driving some 100 miles down south, the glasses had already been snatched up. The thought of having a digital recording of “The Queen in 3-D”—contemporary film footage of the 1953 coronation—without being able to take it in makes me want to jump out and hurl flaming arrows at whoever devised this regionally biased marketing scheme.

What the Bwana Devil! I’ve been trying on various kinds of glasses to take in Channel 4’s 3D fest—but none transport me into the third dimension. Turns out, viewing the weeklong series of films and specials, culminating in a “3-D Magic Spectacular” and a clipfest of “The Greatest Ever 3-D Moments”—requires special goggles that can only be obtained from a certain chain of supermarkets whose reach does not extend to Mid Wales. By the time we got around to driving some 100 miles down south, the glasses had already been snatched up. The thought of having a digital recording of “The Queen in 3-D”—contemporary film footage of the 1953 coronation—without being able to take it in makes me want to jump out and hurl flaming arrows at whoever devised this regionally biased marketing scheme.

“So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (

“So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (