No matter how small our voices, how slight our utterances, millions of us carry on making a record of ourselves and circulating it online. Long gone are the days in which autobiography was reserved for the supposed great and good; now, anyone can flaunt the first person singular, step into the forum and exclaim, “Here I am!” or “Hear me out.” Sure enough, here I go again. Never mind that my record is spun a little less frequently these days, short on that groove I am so slow to get back into. A case of dyspepsia rather than abject discontent. I sometimes wonder, though, in how far the ready access to self-expression and promotion is enabling us to believe that whatever we do or say is quite worth the sharing, that we need not try harder or trouble ourselves to aspire. Now that we can all have our names in lights, provided we supply our own low-wattage bulbs, are we becoming too apt to settle for the publicly unmemorable?

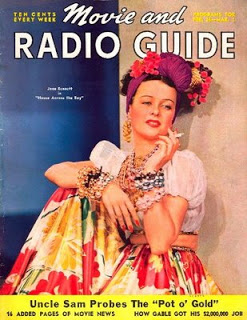

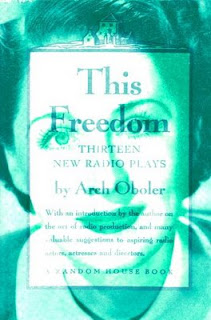

Back in the earlier decades of the 20th century, when folks were more ready to listen and less likely to be heard—by anyone beyond their circles of associates and relations, that is—exemplars were rather more in demand than they are nowadays. No mere American Idolizing, but a veneration of excellence that inspired attempts at emulation. In the 1930s, a decade that gave rise to superheroes and uber-egos—even a glossy magazine like Radio Guide encouraged its readers to aim higher than that knob with which to twist the dial.

Aside from answering questions like “What’s Happening to Amos ‘n’ Andy?” or telling readers “Why Shirley Temple Can’t Broadcast,” the 4 July 1936 issue went so far as to look, jointly with the Edison Foundation,

for the person who will be the greatest benefactor to the human race between 1936 and 1976. We want the man or woman, boy or girl, who will do for the second half of our Twentieth Century what Thomas A. Edison has done for the first half of it. Somewhere in America as you read this, is the second Edison! Is it you? If it is, we want you.

I cannot imagine who would have the nerve to respond to such an appeal and forget all about Amos ‘n’ Andy, then rumored to be leaving the airwaves; nor shall I speculate what Edison might have said about this search for a worthy successor, a campaign published in a less-than-scientific periodical devoted to a medium about which, as Alfred Balk reminds us in The Rise of Radio (2006), the enterprising inventor of the phonograph was less than enthusiastic.

While alive, he was rarely talked of in connection with the medium in whose development he figured; yet he often featured in radio broadcasts of the 1930s and ‘40s. The Radio Guide in which the above call for genius appeared states that “[f]our programs on the air today are about Edison,” among them a biography heard over WCPO, Cincinnati.

On this day, 10 February, in 1947, on the eve of his 100th birthday (and some fifteen years after his death) Edison himself was propped behind the microphone, addressing the audience of the Cavalcade of America program. Titled “The Voice of the Wizard,” the conjuring act was performed by one of the Cavalcade’s freelance scriptwriters, Erik Barnouw, now best remembered as the foremost chronicler of American broadcasting:

“Hello … hello. This is Thomas Alva Edison.” It sounded as if the deaf scientist had picked up the receiver of a spirit telephone to make an urgent point-to-point call:

When I was still on earth, I invented that talk-harnessing machine to show how I felt about … well, occasions in honor of this and that. But now […] I feel differently. Because in a way a broadcast like this is the climax of things I worked at. In a way I can’t help being here. This microphone, and the tubes in your radio—I had a hand in them. So, when those tubes light up and bring you a voice from far off, in a way it’s me talking. And then many radio programs are recorded, for schools, and for broadcasts overseas—all ideas that I fought for. Because the inventions that I cared most about were those that would bring men’s voices across space and time. So—I’d like to tell you the story behind those inventions. A few words for a new age.

As I put it in Etherized Victorians, my dissertation on American radio dramatics, the play bridges, in only a “few words,” the invention of the telegraph, an instrument that in Edison’s youth was already “beginning to bind the world closer,” to the institution of American broadcasting and its contributions to a “new age” of peace:

You who, in a later age, have sat at crystal sets to pick up Pittsburgh or Kansas City, or who, during dark days of World War II have listened by short-wave to London under air attack, you will understand how a seven-teen-year-old boy felt, sitting at his telegraph instrument in Indianapolis. There was already in that room a hint of the radio age […].

As Edison (equipped with the vocal cords of Dane Clark) expressed it in an exchange with his assistant and spouse-to-be, Mary Stilwell (voiced by Donna Reed),

[t]here are barriers between people—and countries—that we almost never break down. Now these things I’m working on, Mary—they’re for breaking down barriers. Talking machines, loud-speaking telephones, talking photography—we’ll have them all! Machines that talk across space and time [….].

The play suggests radio to be at once “talking machine” and hearing aid, a democratic communications apparatus by means of which “truth” is enunciated and disseminated. The institution of broadcasting is thus construed as the product and propagator of “the American Idea,” for which “the whole world is better off.”

We do not have to resort to thaumaturgy or otherworldly telephony to be “talking across space and time” these days; but I sometimes wish we were more receptive to the marvel of this means and expressed ourselves more grateful at the potentialities we so often squander by billboarding the trivial. While I can neither “help” being prolix nor “being here,” I am making some amends today by refraining from relating just why Shirley Temple could not broadcast …

Staying out of touch has never been easier. We’ve all got our personal teleporters to spirit us away from the here and now. Technology is making it possible for us to remove ourselves from our communities, to stay at home not watching the world go by. Instead, we can revel in bygone worlds. Hundreds of satellite channels are serving up seconds. Before you know it, you quite forgot what time it is that you just passed. Isn’t it high time for Sally Jessy Raphaël to stop gabbing? Eight years ago she went off the air; but there she is, chatting away on British television, her owl glasses unscratched by the sand of time.

Staying out of touch has never been easier. We’ve all got our personal teleporters to spirit us away from the here and now. Technology is making it possible for us to remove ourselves from our communities, to stay at home not watching the world go by. Instead, we can revel in bygone worlds. Hundreds of satellite channels are serving up seconds. Before you know it, you quite forgot what time it is that you just passed. Isn’t it high time for Sally Jessy Raphaël to stop gabbing? Eight years ago she went off the air; but there she is, chatting away on British television, her owl glasses unscratched by the sand of time.  This is a day for disguises, and a night of unmasking. A time to let yourself go, and a time to let go of something. A night to make an ass of yourself, and a morning to mark yourself with ash. Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras, Fastnacht. Back where I come from—Germany’s Rhineland—carnival is a major holiday, an interlude set aside for delusions, for letting powerless misrule themselves: laborers parading in the streets without demanding higher wages, farmers nominating mock kings and drag queens to preside over their revels; women storming the houses of local government to perform the ritual of emasculation by cutting off the ties that hang from the necks of the ruling sex. It is a riotous spectacle designed to preserve what is; a staged and sanctioned ersatz rebellion that exhausts itself in hangovers.

This is a day for disguises, and a night of unmasking. A time to let yourself go, and a time to let go of something. A night to make an ass of yourself, and a morning to mark yourself with ash. Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras, Fastnacht. Back where I come from—Germany’s Rhineland—carnival is a major holiday, an interlude set aside for delusions, for letting powerless misrule themselves: laborers parading in the streets without demanding higher wages, farmers nominating mock kings and drag queens to preside over their revels; women storming the houses of local government to perform the ritual of emasculation by cutting off the ties that hang from the necks of the ruling sex. It is a riotous spectacle designed to preserve what is; a staged and sanctioned ersatz rebellion that exhausts itself in hangovers.

Before settling down for a small-screening of Inherit the Wind, I twisted the dial in search of the man from whose contemporaries we inherited the debate it depicts: Charles Darwin, born, like Abraham Lincoln, on this day, 12 February 1809. Like Lincoln, Darwin was a liberator among folks who resisted free thinking, a man whose ideas not only broadened minds but roused the ire of the close-minded–stick in the muds who resented being traced to the mud primordial, dreaded having what they conceived of as being set in stone washed away in the flux of evolution, and resolved instead to keep humanity from evolving. On BBC radio, at least, Darwin is the man of the hour. His youthful

Before settling down for a small-screening of Inherit the Wind, I twisted the dial in search of the man from whose contemporaries we inherited the debate it depicts: Charles Darwin, born, like Abraham Lincoln, on this day, 12 February 1809. Like Lincoln, Darwin was a liberator among folks who resisted free thinking, a man whose ideas not only broadened minds but roused the ire of the close-minded–stick in the muds who resented being traced to the mud primordial, dreaded having what they conceived of as being set in stone washed away in the flux of evolution, and resolved instead to keep humanity from evolving. On BBC radio, at least, Darwin is the man of the hour. His youthful